Boobs are Not the Enemy: Video Games and the Male Gaze

Probably the people watching my street racing movie like fancy cars, so they will appreciate the scene with the villain’s car. But now suppose I make another movie about a small-town high school teacher rallying the community for a local cause. When I first show the teacher driving to work, I use the same cinematic tricks I did in the other film - slowly panning along the car while playing dramatic music. Then the teacher gets to the school, and the story moves on.

Someone who really likes cars may still enjoy this scene, but to most people it’s going to be distracting at best. The car isn’t important to the story at all - why is it receiving so much attention? Why would I assume that the audience of this completely different film would be into cars? If I keep doing this, with more and more films on various subjects all treating cars in this same way, people who don’t care about cars may start to get annoyed with my work. They might feel that I’m being exclusionary in my film-making, privileging part of the audience over the rest for no clear reason. Plenty of people aren’t obsessed with cars - why can’t they enjoy my low-budget monster movie or my railroad magnate biopic too? Why do I insist on shoving in these totally distracting segments that damage the experience for them?

When the question is brought to me, I respond with confusion. “What’s wrong with fancy cars?” I ask. “I like fancy cars, and so do a lot of people.” I point out that it’s Hollywood, and people live in fancy houses and wear fancy clothes too, and nobody seems to have a problem with that. It’s just part of the expectation of movies.

I am, of course, completely missing the point. The problem isn’t the presence of the fancy car - it’s how it’s presented. It’s the framing and the context. It’s the way I focus on details not because they’re important to the film, but because I think the viewer will enjoy them. It’s the assumption that the viewer has particular tastes, and the implication that the enjoyment of anyone with different tastes is unimportant.

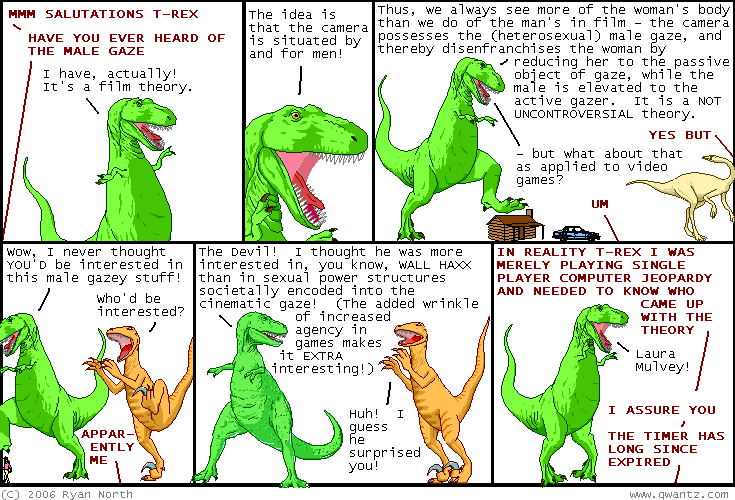

Replace “fancy cars” with “hot women”, and you have the male gaze.

(I hate the term “male gaze”, by the way. It’s misleading, exclusionary, and heteronormative. But it’s the term that people know, so it’s the one I’m going to use.)

A common response to complaints that a particular work focuses unnecessarily on female hotness is to point out that the men in the work are unrealistically hot as well. This is true, but it’s changing the subject. The issue isn’t the hot, it’s the focus.

When the male gaze is in play, the attractiveness of male and female characters is framed in very different ways. Men are presented as targets of identification or rivalry - the audience is expected to either want to be him (like with the hero of my street racing film) or defeat him (the villain of my street racing film). Either way, a male character is presented as the audience’s peer, with power and autonomy.

Women, on the other hand, are presented as targets of desire. The audience is expected to want to possess her (like with the cars in my film). Positioning a character in this way undercuts her autonomy, no matter how the work is written. She’s not being presented as the audience’s peer - she’s a prize. It’s very difficult, not to mention unappealing, to identify with a female character who’s being framed as an object of the audience’s presumed lust. (This, by the way, is part of what’s meant by “objectification.” The cars are mere objects, with no will of their own, and an objectified character is one that’s treated the same way.)

Here’s a panel from the first issue of Red Hood and the Outlaws from DC’s New 52 event in 2011:

Why is this panel problematic? It’s not because the woman (Starfire) is hot. The man (Roy) isn’t bad himself. The problem is that Roy is doing what a normal human being does on a beach - he’s relaxing. Starfire, on the other hand…

“Why is she contorting her body in that weird way? Who is she posing for, because it doesn’t even seem to be Roy Harper? The answer, dear reader, is that she is posing for you. . . . Because it’s not about what Starfire wants. It’s about what straight male readers want. And they want to see Starfire with her clothes falling off. And hey, hey – there’s nothing wrong with that specifically, but let’s be honest about what’s happening and who we’re serving (or not serving) and at whose expense.”

—Laura Hudson, The Big Sexy Problem with Superheroines and Their ‘Liberated Sexuality’

“‘Is this new Starfire someone you’d want to be when you grow up?’

*she gets uncomfortable again* ‘Not really. I mean, grown ups can wear what they want, but…she’s not doing anything but wearing a tiny bikini to get attention.’

. . . . See, it’s not about what they’re wearing, though that can influence things. What makes a hero is WHO they are, the choices they make and the things they do. If my 7 year old can tell what you’ve done from looking at the pictures…why can’t you see the problem here?”

—Michele Lee and her seven-year-old daughter, Dear DC Comics

Starfire’s hotness isn’t the problem. The problem is that her hotness is emphasized in a way that separates her from the reader and turns her into the Other.

When people play Uncharted, the assumption is that they will identify with Nathan Drake. It’s a power fantasy - the player can blow off steam as a resourceful, charismatic treasure hunter. Okay, how about Tomb Raider? After all, Lara Croft is also a resourceful, charismatic treasure hunter.

“‘When people play Lara, they don’t really project themselves into the character,’ Rosenberg told me at E3 last week when I asked if it was difficult to develop for a female protagonist.

‘They’re more like “I want to protect her.” There’s this sort of dynamic of “I’m going to this adventure with her and trying to protect her.”’

So is she still the hero? I asked Rosenberg if we should expect to look at Lara a little bit differently than we have in the past.

‘She’s definitely the hero but— you’re kind of like her helper,’ he said. ‘When you see her have to face these challenges, you start to root for her in a way that you might not root for a male character.’”

—Jason Schreier, You’ll ‘Want To Protect’ The New, Less Curvy Lara Croft

Become the male hero. Help the female hero. That’s what the male gaze does to video games.

Video games are fighting a long, slow battle toward gender equality. They’ve made a lot of progress, but it’s still a male-dominated industry and consumer base. It’s very easy in that sort of environment for creators to unintentionally bake assumptions about the audience into their work. But that doesn’t mean that every attractive female game character is a product of the male gaze. It’s all in the framing and context.

Dragon’s Crown is an upcoming action RPG brawler by Vanillaware. When publisher Atlus released a gameplay trailer starring the game’s Sorceress character, who makes Jessica Rabbit look understated, there was a bit of a hullabaloo.

“That’s actually something that made its way into a basically finished video game, fucking lol! Some juvenile delinquent kid in my 5th grade class used to draw girls that looked like that (only without the creepy blank, featureless samefaces and wizard hats), and I think he was actually better at it. I also think he’s in jail now. This is amazing.”

—Forum post by Shaylyn Hamm, Environmental Artist at Gearbox Software

Without context, it’s easy to assume from this trailer that Dragon’s Crown is just puerile fantasy for teenage boys, and the Sorceress merely its central cheesecake. But here’s the thing - the Sorceress is just one of six playable characters. Three of them are male, three are female, and all of them embody a different exaggerated archetype. Here’s what Vanillaware founder and lead artist George Kamitani said about why Dragon’s Crown’s characters look the way they do:

“I believe that the basic fantasy motifs seen in Dungeons & Dragons and the work of J.R.R. Tolkien have a style that is very attractive, and I chose to use some orthodox ones in my basic designs. However, if I left those designs as is, they won’t stand out amongst the many fantasy designs already in the video game/comic/movie/etc. space. Because of that, I decided to exaggerate all of my character designs in a cartoonish fashion.

I exaggerated the silhouettes of all the masculine features in the male characters, the feminine features in female characters, and the monster-like features in the monsters from many different angles until each had a unique feel to them.”

—George Kamitani, as quoted in The Artist Behind Dragon’s Crown Explains His Exaggerated Characters

Or, as Tycho of Penny Arcade puts it:

“The only characters here who aren’t fucking mutants are the Elf and the Wizard, who are there to calibrate the player; everybody else is some fun-house exponent of strength or beauty stretched into some haunted sigil. Iconic isn’t even the word - they don’t evoke icons, they are icons. They’re humans as primal symbols.”

—Tycho, Character Selection

This is not a case of a female character being sexualized for the audience’s benefit simply because she’s female. Dragon’s Crown has a consistent aesthetic of essentialism through overstatement - the Sorceress fits into that motif. Her archetype happens to be what Bob Chipman called the “Voluptuous Magic User”, but it is one of many, and just like with Jessica Rabbit (or the Widow Chastity in Stacking) it’s part of her character. It’s not gratuitous and it doesn’t make assumptions about the audience.

Contrast this with, say, Ginny, a minor NPC from RAGE. This is a promotional image, but it’s an actual screenshot - this is how Ginny can be found standing in the game.

At first glance, Ginny’s just leaning against a wall. But she’s actually standing in a fairly unnatural way in order to sick her chest out and show off her legs. Try standing that way - it is not comfortable. Ginny isn’t relaxing; she’s posing. There’s nothing in the game that suggests that this is part of her character. It doesn’t fit into any overarching message or theme. It’s not a believable human action in the context in which the character performs it. Ginny’s posing just so the player can see her pose.

Or how about this quick scene with Miranda from Mass Effect 2? While talking to Shepard, Miranda leans against her desk in a slightly weird way. A moment later, the camera switches angles, and we realize why she’s standing like that.

Again, she’s posing for the camera - for a camera that isn’t even there until after she strikes the pose.

This is the male gaze in action. In these moments, the game says, “Here’s a treat for all you appreciators of the female form.” If it occurred to the creators of these moments that a portion of their audience might not fall into that group, it doesn’t seem to have dissuaded them. These moments send a message that the game isn’t for people who don’t want to stare at women’s bodies. Those people are not the target audience. They are not welcome. It doesn’t matter if everything else about the game appeals to them.

“I did a day-long workshop called Girls in Game Design. . . . I had 25 women in the class. In the second half of the class, I brought in five machines, and I put in five games, Warcraft, Diablo, Halo, Half-Life, and Max Payne. We’re talking top-selling games, here. We’re talking record-breaking, highly recommended, highly recognized titles. And one of those games was put on each machine. There were five women in a group, and I put the group in front of the machine. It became clear all of a sudden that none of them had played any of those games. These were women in the game industry. They had not played those games. I was floored.

I said OK, you’re going to play them. By the end of the day, they had voted Warcraft as their number one favorite game, and they were all going to go out and buy it and play it. So it wasn’t the gameplay that was stopping the women from playing the game. Something else had stopped them, at the door, from playing these titles before. That’s what this industry has to identify: What is stopping women from picking that box up off the shelf?”

—Sheri Graner Ray, as quoted in GDC Q&A: Women’s advocate, industry hero, Sheri Graner Ray

There are a lot of complex reasons why women don’t play games the way men do. But surely moments of blatant male gaze are part of it. If someone tries to get into gaming, but frequently comes across jarring reminders that they are wandering into territory not meant for them, it’d be completely understandable for them to get frustrated and give up.

This kind of barrier is completely unnecessary. All it takes to avoid it is an open mind about the audience of a work. The Sims drew a huge female audience. World of Warcraft did the same thing. Neither of these games was designed specifically for women. These games simply didn’t exclude women. These games were made for people.