Mirror's Edge: What Went Wrong and Why

Mirror’s Edge is a Bad Good Game. The foundation is solid: players take the role of Faith, a genuinely badass woman with a non-exploitative, unconventionally beautiful design whose motivations revolve around survival and protecting her sister. Faith parkours her way around an unnamed city of bright colors and austere beauty, and is trained in a variety of disarm techniques should she encounter armed attackers she can’t simply outrun. Sounds good, right?

In practice, however, the game is plagued by a wealth of bad design decisions. Typical of a Bad Good Game, reception was mixed, with some really liking it while others hated it. The game’s narrow appeal is the result of specific design choices - so let’s look at some of the things the game did wrong and the misguided design philosophies underlying the errors. (To highlight these decisions, I will be comparing the game to a few others with related mechanics - mostly Prince of Persia.)

Even on the easiest difficulty, the game doesn’t hold the player’s hand at all. Faith has absolutely no qualms about stepping right off the edge of a skyscraper’s roof, and if you’re even slightly off with your maneuvering, you will fall to your death. Wallruns are especially problematic - it’s very, very easy to start a wallrun incorrectly and get shorted on the distance it covers, and thus fall before you make it to your target. It doesn’t even feel predictable - there were several wallrun sections throughout the game that I had to try over and over, and I couldn’t even tell you what I did differently when they finally went right.

To cast this in a bit sharper contrast, let’s compare it to Prince of Persia. If you put the Prince in the right place and execute the right action, you’ll get where you’re trying to go. And if you walk the Prince off a ledge, he’ll drop down and grab on rather than just step off into nothing and plummet.

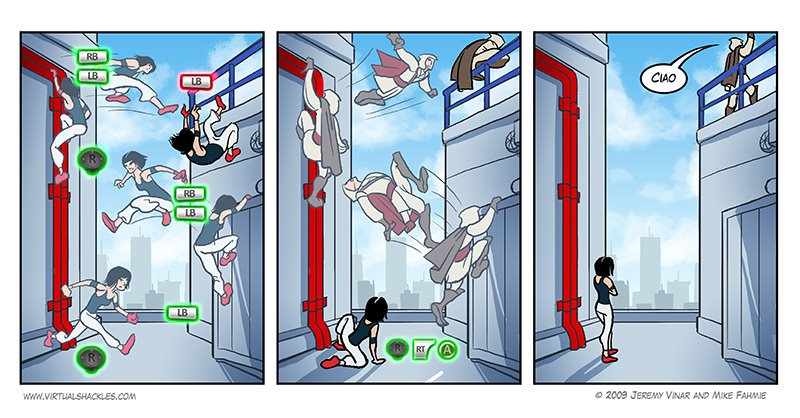

Mirror’s Edge has a fairly standard tutorial. A couple of characters step the player through the abilities in Faith’s arsenal, and they must all be executed successfully in order to proceed. The problem - and it’s a common one - is that they are presented rapid-fire, one after another, with nothing to actually help the player internalize them. The combat abilities in particular are unlikely to be recalled when the player finally gets into a fight some time later - it sure took me a while to remember that I had slide- and jump-kicks at my disposal.

Abilities won’t stick unless the player can use them in a memorable way. It’s much more effective to introduce them a bit more gradually, testing them in real gameplay situations - which Prince of Persia does.

Mirror’s Edge has two ways to give the player hints on where to go next. An optional feature called “Runner Vision” highlights important objects in Fath’s path by coloring them bright red, and the “Look” button causes Faith to point herself at her next goal.

That’s the theory, anyway. Both systems behave strangely - I repeatedly saw ladders turn red as I was already climbing them, and Look would often point me at a wall or ceiling, or simply do nothing at all. Worse, the number of cues gradually goes down throughout the course of the game. Fewer and fewer red objects appear, and the goals designated as Look targets become more widely spaced. These trends culminate in a large atrium late in the game, in which Faith needs to climb up several floors to reach an air shaft. In this area, nothing at all is colored red, and Look uselessly points straight up to the air shaft. The player is totally on their own to figure out how to reach it.

What justification can there be for limiting Runner Vision as the game goes on? It is an optional feature. The player who wants to figure out where to go on their own is free to turn it off - and actually can’t turn it on if playing on Hard. Someone playing on Easy with Runner Vision enabled wants the cues. Taking them away from that player is just cruel.

Bringing Prince of Persia in as a comparison again, that game’s Compass ability causes a ball of light to illustrate the exact path the Prince needs to take to reach his next objective. There’s never any guesswork if the player doesn’t want there to be.

These three issues all share a common philosophical cause: Mirror’s Edge is deliberately anti-Easy in its design. It demands a great deal from the player and seems to resent the very idea that some players might need a bit more help. There’s nothing wrong with providing a high level of challenge - indeed, Prince of Persia was frequently critisized as being too easy, even by those that liked it. The problem is that this higher level of challenge belongs on Hard mode - but I have just described the way the game plays on Easy. Easy should be easy.

There’s been some discussion of the differences between the death mechanics in Mirror’s Edge and Prince of Persia. In both cases, the effect is that the player is moved back to a checkpoint - but the presentation differs. Faith plummets, faster and faster, until the screen goes black and the player is treated to the sickeningly plausible sound of a wet crunch. A quick load-screen later, Faith stands again at the last checkpoint. The Prince, by contrast, technically never dies - whenever he begins to fall, his companion Elika uses some quick teleportation to bring him back to the last solid ground on which he stood. The result is similar - but the psychological impact is incredibly different. Prince of Persia’s technique soothes the player, demonstrating that the game is well aware that the player can’t possibly get everything right on the first try, and that this is not cause for shame. Mirror’s Edge, on the other hand, rubs the player’s nose in the consequences of their inadequacy, making sure they know exactly what they have done to Faith.

“For some players, the sense of total failure that accompanies Faith’s dramatic deaths outweighs the sense of relief and accomplishment that they feel when she finally makes it to the next checkpoint. And, by comparison, Elika’s constant lifesaving presence must make the Prince feel a lot less heroic and death-defying to some.”

—Adam LaMasca, Failing, Falling, and Feeling

There are other differences, too. Prince of Persia’s death mechanic is unusual in that it offers a diegetic reason for the fact that the player is free to try again, while Mirror’s Edge, like most games, offers no in-universe explanation whatsoever, and consequently suffers from the usual immersion-breaking problems. But also, because Mirror’s Edge effectively rewinds time to when Faith stood at the checkpoint, it actually undoes progress - sometimes including cutscenes or character speeches, which must now be sat through again. And the checkpoints are definitely further apart than the Prince’s solid grounds.

The philosophical reason for this is related to the game’s anti-Easy stance. If the player needs to earn their fun, then there must be consequences for failure. The unpleasantness of the consequences in Mirror’s Edge stem more from their psychological aspect than their gameplay effect, but they are punishment just the same, and increase player frustration.

Mirror’s Edge takes place in a huge, gleaming city. To runners like Faith, the rooftops are a playground. But to the player, they are a strangely linear one. The city is not a full open world, but rather a series of disconnected levels, in which there is always exactly one way forward (not counting the minor differentiation of occasional shortcuts). There’s not much in the way of exploration - it’s just about finding the part of the local environment you’re supposed to interact with.

Faith spends about half her time trying to reach specific destinations, and the other half evading pursuit and escaping to safe territory. But even when Faith is running from rather than running to, there’s only one way to go. The only real difference is that the path is harder to find, both because of the time pressure added by the pursuit and because the game usually only explicitly shows the player what to flee from, rather than where they should try to go.

The philosophy underlying this is the same one that usually underlies option restriction - by limiting the player’s choices to a single path, the designers exert greater control over the game experience. This is often a perfectly valid design decision, but is much more questionable in a game whose central mechanic is freedom of movement. It’s also at odds with the philosophy behind the demanding and precise controls mentioned earlier, which theoretically grant the player more freedom - but because the environment is so constrained, they mostly just create additional opportunities to fail.

In Assassin’s Creed, Altair can run and climb freely around a few decently-large cities. He has specific targets, but the player is free to devise their own paths and figure out their own escape routes. And the controls are streamlined - point Altair in a direction, and he’ll climb as necessary.

The single most problematic aspect of Mirror’s Edge is the combat. Nowhere else is the game’s design philosophy actually in conflict with itself.

Faith is a runner, not a fighter. Parkour isn’t about fighting - it “can be compared to some martial arts, but without the violence; in the fight-or-flight response, parkour is the flight.”

Faith’s ability set is based around moving quickly and disarming opponents when combat can’t be avoided. She can use guns she takes from her attackers - but while carrying a gun, she moves slowly, she can barely jump, and she can’t climb at all. Whenever Faith holds a gun, it feels wrong. And in fact, the game has an achievement/trophy called “Test of Faith” which is earned by completing the game without ever shooting anyone.

But the timing window on disarming opponents is vanishingly small. It’s easy to disarm someone who’s facing away, but this opportunity almost never presents itself - anyone Faith attempts to sneak up on will somehow detect her and turn around before she reaches them. And while Faith’s tactics are best suited to dealing with one or two enemies at a time - as her own allies remind her - the game has a tendency to throw several enemies at her simultaneously. Even if she manages to disarm one, the others gun her down while she completes the animation.

Only after beating the game (and earning Test of Faith) did I realize something - usually when Faith comes under attack, one or two of the enemies approach her separately from the others who hang back in a group. The game is giving Faith a gun. She is supposed to take it in single combat, and then use it to kill the rest of the group - despite the fact that everything else about the game discourages the use of guns.

Philosophically, this is a result of divided vision. The game encourages quick disarms and combat avoidance - and then forces the player into firefights. The game disagrees with itself about how it should be played, leading the player into frustration.

“I think we probably placed too much emphasis on not using the weapons by adding things such as the ‘Test of Faith’ Achievement. This was intended as something for more hardcore players on a second run-through, but it seems to have encouraged many to attempt it the first time, with the result that they find the game harder and some areas frustrating. . . .

It does seem like a lot of people went for the Achievement, though. Of course, we have to wait for the final figures, but I think it is very interesting that a lot of players were quite happy with the idea of not using guns at all. It certainly shows that there is a lot more to the first-person genre than just shooting, and, yes, if we do make a sequel, it would definitely influence the design.”

—Producer Tom Farrer, Mirror’s Edge Afterthoughts

A sequel has, in fact, been announced. What can be expected from this sequel depends completely on what DICE has learned from the first Mirror’s Edge. It’s a pretty experimental game, and the whole reason we experiment is to learn - and often, if we are open-minded, failures teach us more than successes. If DICE looks in the right places, Mirror’s Edge has a lot to teach them.

In one scene, Faith eavesdrops on a phone call from an air shaft. Once the person she was spying on leaves his office, Faith inexplicably drops into the office rather than retreating the way she came. In doing so, she apparently triggers an alarm, because she is immediately under pursuit - if she doesn’t get out of the area quickly, a large group of security personnel storm in and shoot her dead.

When I played this scene, I found what appeared to be a viable escape route, but my maneuvers were unsuccessful - they ended in a wallrun, and time after time Faith simply failed to grab on to the ledge on the other side, fell several feet and had to start over. But the pursuing security personnel don’t give much time to experiment - after two attempts, they burst in, and Faith is as good as dead.

Because of the lack of red objects, and Look not pointing me anywhere particularly useful, it was not at all clear to me whether I was failing to do the correct thing, or simply trying something completely incorrect. With all the wasted time dying and loading from the checkpoint, and the short window in between, it was very difficult to explore enough to be sure. It’s just not possible to quickly figure a place out when being shot at.

I kept trying, and finally Faith did grab the ledge, and I was able to continue. But it didn’t really feel like I had figured anything out. I had just tried enough times and gotten lucky.

This one scene captures nearly everything wrong with Mirror’s Edge. When these factors don’t occur - when repeated death doesn’t break the flow, and the player either has the time to look around and figure things out or is given the information they need to move and react quickly, and can string together a long sequence of running and jumping and climbing and running, building momentum and flying effortlessly through the city - the game works incredibly well.

Mirror’s Edge delivers this experience far too rarely, and I cannot in good conscience recommend the game. Play Prince of Persia or Assassin’s Creed or Uncharted 2: Among Thieves instead. But if Mirror’s Edge 2 manages to consistently provide the experience described above, it will be a fantastic game, and the existence of Mirror’s Edge will be completely justified. It will all have been worth it.