Faith in the Possibility of Good: A Close Reading of Q.U.B.E: Director's Cut

Spoiler warning for Q.U.B.E: Director’s Cut and Portal.

The most subversive story I’ve seen lately was in a game that launched without one.

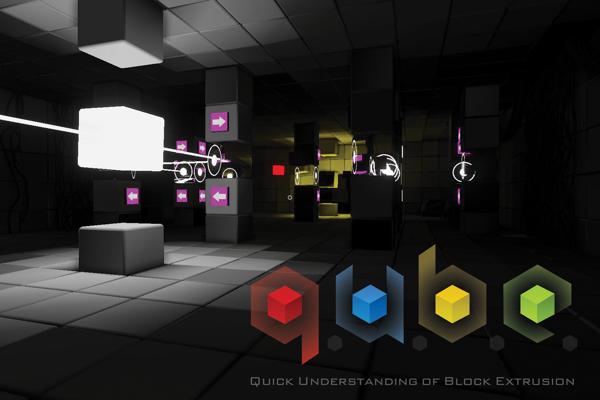

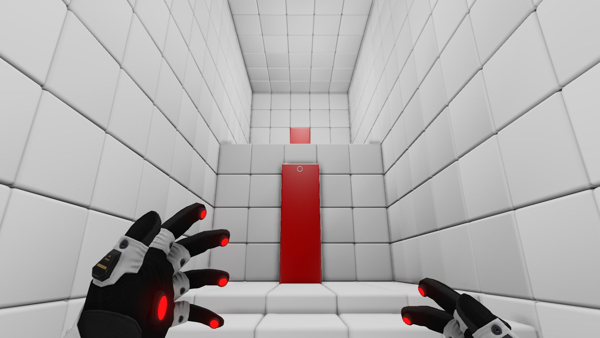

Q.U.B.E. is a first-person physics puzzler with obvious Portal influences that first came out in December 2011. Reviewers praised its puzzle mechanics but complained that it lacked a story. The player character simply wakes up in a strange room and walks forward solving puzzles until they are done.

In May 2014, Q.U.B.E: Director’s Cut was released. This version made several changes including improvements to graphical effects and pacing of the puzzles. The biggest change was the addition of a story told via radio transmission voiceovers delivered expertly by Rachel Robinson and Rupert Evans.

The impression I get from looking at reviews and anything else I can find written about the game online is that most folks moved on after the original version. Review outlets published perfunctory updates saying that yup, the game is still a fun puzzler, and yes, now it has a plot tacked on as well. Almost no one seemed to have anything deeper to say than that.

Well, I do. The story in Q.U.B.E: Director’s Cut surprised me a great deal. It’s well-crafted and expresses a clear and uplifting message that serves as a fascinating response to other prominent games. So I think it’s worth a closer look.

I won’t be spoiling any of the puzzles, but I will spoil the full story. I’m going to give an overall plot summary, discuss the context in which the game was released (spoiling some significant plot elements of Portal along the way), and then dive into a detailed story analysis including a lot of the dialog. This is a good game and if you’re interested in physics puzzlers and intrigue plots I absolutely recommend you check it out - ideally before reading any further. It’s fairly cheap on several platforms and just a few hours long. The same applies to Portal.

The Plot Summary

Okay, here’s the plot summary. The player character wakes up in a strange room and hears a radio transmission from a woman called Nowak. She tells the player character that he (and the character specifically is a ‘he’ - we’ll get into that in the story analysis) is an astronaut on a space mission but the journey has caused amnesia. He’s in a giant structure - the Qube - hurtling through space toward Earth. If it hits, it’ll wipe out all life on the planet. So he’s got to stop it by solving its puzzles.

Radio transmissions from Earth can’t reach the Qube’s interior, but Nowak’s on the International Space Station and her orbit will take her in and out of communication range. As the player character moves forward solving puzzles, Nowak occasionally establishes a connection and speaks some more before eventually moving out of range. She implores the player character to have faith and keep moving forward so that he might save the whole world. However, in between these transmissions another voice establishes contact - a man who identifies himself only by the number Nine-One-Nine. He claims that Nowak is lying - the Qube isn’t in space; it’s an underground testing facility where the player character will be experimented on and then abandoned or killed. The hero story is a lie to encourage cooperation and the player character should not believe it.

As the player character progresses through the puzzle rooms, Nowak and Nine-One-Nine periodically add flavor and raise the stakes. Nowak assures him that he is damaging the Qube; Nine-One-Nine assures him it’s a lie. No conclusive proof either way is on offer. Finally the player character reaches what Nowak claims is a launch bay, and she tells him he must get in one of the escape shuttles because the Qube is coming apart completely. Nine-One-Nine claims it’s a trap and that the “escape shuttle” will head right into an incinerator.

When the player character gets in, the shuttle launches and emerges into space - Nowak was telling the truth. Free of the Qube, the player character can now receive transmissions from Earth and is contacted by his wife and then the President. Nine-One-Nine is revealed as another astronaut who was lost and presumed dead several years earlier and has been driven mad by isolation in deep space, but now that he’s been found he can be rescued and brought home. The President thanks the player character for persevering despite any doubts and says that’s how greatness is accomplished - by “having faith in the possibility of good.”

So, that’s the game. It’s a happy ending, but to understand its significance it’s important to know the context in which it was created. This story seems to be a direct response to common tropes of the time - and specifically to Portal.

The Context: Post-Portal Depression

“One of the complaints that many reviewers seemed to share about Toxic Games’ debut first person puzzler, Q.U.B.E., was that it lacked the character and personality of Portal but shared a similar environment. . . . [Narrative designer] Sam [Mottershaw] told us that he was quite frustrated at the fact that a lot of reviewers said that the game lacked something, mostly because they had been spoiled by the wonderful character interaction and narrative of Portal which features the highly memorable GLaDOS, of course.”

—Chris Priestman, Original Story For ‘Q.U.B.E.’ Was Pulled At Last Minute, Featured GLaDOS-Like Voice Over

Ironically, Q.U.B.E. originally was slated to have a story, and just like Portal it was to feature a female AI speaking to the player character.

“[Mottershaw designed] a whole narrative thread to Q.U.B.E. which was pulled from the game so that it could be released before Christmas. . . . The main remaining [piece] is right at the start of the game when the walls close in on the player to give a sense of hostility and claustrophobia. These kinds of effects and continuing themes were originally included throughout the entirety of Q.U.B.E., most notably with the input of a female AI character voiced by Emily Love – a friend of the development team.”

—Chris Priestman, Original Story For ‘Q.U.B.E.’ Was Pulled At Last Minute, Featured GLaDOS-Like Voice Over

When Toxic Games went back to add a story for the Director’s Cut, they abandoned Mottershaw’s plan and took a different tack - probably a wise choice given all the Portal comparisons that had already been made. Here’s the explanation found on the game’s press page and Steam page:

“To reboot the narrative, Toxic Games brought in industry veteran Rob Yescombe, writer on franchises including CRYSIS, ALIEN: ISOLATION, STAR WARS and PS4’s upcoming RIME; winner of Best Thriller Screenplay at the Creative World Awards, and the screenwriting Award of Excellence at the Canada International Film Festival.

‘The Director’s Cut is a single-location thriller,’ says Yescombe. ‘It’s about figuring out what the Qube is, and why you’re inside it. You’re told you are an astronaut inside some kind of alien structure hurtling towards Earth, but it’s also about something deeper than that.’”

At first blush, Yescombe appears to have - like Mottershaw before him - aped Portal’s narrative hooks. Both Portal and Yescombe’s story feature a disembodied female voice (respectively, GLaDOS and Nowak) directing the player character to move forward and solve puzzles for a promised reward (respectively, cake and saving the world). Mounting evidence suggests this is a lie masking malicious intent, but each game’s structure gives the player no real choice but to proceed anyway.

Halfway through Portal, GLaDOS finally betrays the player character and leads her into an incinerator. Yescombe’s story foreshadows that Nowak will do the same (we’ll get into the specifics when we reach those parts in the story analysis) to take advantage of the obvious Portal parallels and set up an untwist by ultimately revealing Nowak to have been honest and benevolent all along.

Why do this? Here’s the explanation attributed to Yescombe, also from the game’s press page and Steam page:

“We are conditioned to expect death and doom. We’re resigned to it. At its heart, this story is about that state of mind and how it effects the way we view our experiences, in games and in life. The Director’s Cut will feel either heroic or unnerving, depending on your own personal trust issues.”

Portal is one of several prominent games from this era which feature mission givers or apparent allies who betray the player character or otherwise spend a lot of time forcing the player down unwise paths toward destruction. (To avoid unnecessary spoilers, I’m not going to name any other specific examples, but you can find several very big games released between 2007 and 2014 sprinkled through this list.) While Portal plays the twist for dark comedy, other games use it as a deconstruction of option restriction or a criticism of players’ willingness to commit virtual murder and mayhem just because their game tells them to.

Q.U.B.E: Director’s Cut rejects this fatalism and instead presents a story where you actually can be the hero, where there is real hope, and where the people who seem to be trying to help you are actually trying to help you. It leads you to expect or fear the same old deconstruction - magnifying the impact and relief when it turns out to be a reconstruction instead. And as Yescombe notes, there are implications that extend well past the realm of games and into real life.

The difference between the opposing worldviews - the assumption of “death and doom” (as Yescombe puts it) versus “faith in the possibility of good” (as he has Nowak put it) - is the core of Q.U.B.E: Director’s Cut’s story. Just about every line of dialog from start to finish builds up to it. So now I’m going to dive in to a full story analysis, starting at the very beginning.

Story Analysis: The Opening Scene

The game begins with the player character regaining consciousness. A radio transmission of a woman’s voice can be heard.

“And what if it didn’t kill him? With all due respect, your best guess is still just a guess. We need to have faith in the possibility of good. Wait, hold on - his oxygen consumption is going up. I think he’s alive. He’s conscious.”

There’s a surprising amount packed in to these first few sentences, though it’d be difficult for a first time player to catch it all. There’s too much the player is piecing together for it to be clear what’s significant. They are taking in the unfamiliar setting and the strange gloves their character is wearing. They don’t know who this woman is, who she’s talking to, or who she’s talking about. We’ll come back to these lines in a moment once there’s a bit more context.

The woman then addresses the player character directly and clarifies a few things. She tells him that he’s been unconscious for fifteen days and it was feared that he was dead, but that his “life suit” kept him alive. Unfortunately, she can’t link into his camera or receive from his radio, so he can’t communicate back and she can’t tell what he’s doing - she can’t even be sure he’s hearing her, or how badly he’s been affected by his journey.

“If you’re feeling confused or disoriented, you should know that deep space travel can do you pretty serious psychological damage… especially to your memory. Even a few hours out there in the dark can cause permanent problems. I’m gonna be honest with you - Mission Control are concerned you might have no idea who you are or why you’re in there. If that’s true, I have some difficult facts for you.”

Technically, it’s never made clear whether the player character actually does suffer from amnesia. He’s a silent protagonist and never does anything that confirms or rules out the possibility. But I think the intended reading is that he is indeed amnesiac, as this puts him in the same situation as the player and thus makes him easier to empathize with. Player and character both only know what they’ve seen and heard since waking up.

The voice claims that the player character is “a very long way” from Earth, inside a mysterious structure that’s headed through space and will crash into the Earth in just a few hours, and that this will wipe out all life on the planet. His job is to “decipher and dismantle” the structure before that happens and save the world.

She then identifies herself as Commander Nowak, an astronaut on the International Space Station and the only human in transmission range, at least when the station is at the right portion of its orbit. Shortly thereafter, her signal starts breaking up.

“Just stay calm and keep your head straight until I get back into range. Okay, this is it: I’m orbiting out of range now. I’ll be back soon. Just remember what I’ve told you… and believe it.”

So, that was a lot. What a first-time player is likely to take away from it is the infodump that contextualizes the player’s actions - they’re an amnesiac astronaut on a mysterious spaceship, they need to solve puzzles to save the world, and they’ll occasionally hear from Nowak along the way. But along with that come some implications that say a lot about Nowak’s personality and her role in the story.

The player character was sent alone into space to stop the Qube and save the world but has been unconscious for over two weeks and now there are only a few hours left. Mission Control has apparently given up, but Nowak hasn’t. Nowak’s still trying to reach the player character because he might not be dead and there’s still a chance to save the world. And if he is alive, he may not know what’s happening, and if so he’ll need her guidance. And it turns out that he is alive, and does need her guidance, and she does reach him in time. If she’d stopped trying, the world would have ended when it didn’t need to.

Right from the beginning, Nowak is established as the voice of pragmatic optimism. She doesn’t give up just because the odds are against her. She has “faith in the possibility of good” - she does things because they might succeed. We’re going to come back to this a lot in her future dialog - just about every time she contacts the player character, she mentions faith or that she’s keeping her “fingers crossed.”

It’s also worth noting that Nowak’s first lines explicitly gender the player character as male. This may seem like a strange choice in a first-person game with a silent protagonist and no mirrors. The only visible part of the player character’s body is covered by gloves and the dialog could easily have been rewritten to avoid the use of gendered pronouns - why prevent non-male players from projecting themselves into the game? There is a reason for this, but it comes later. For now I’m just acknowledging that this may seem strange to the first-time player.

Finally, Nowak’s speech ends with an exhortation for the player character to “believe it.” While it is crucial to the survival of Earth that the player character does accept his mission, from a storytelling perspective it’s a slightly odd thing to say here. At this point, the player has no reason not to believe Nowak. The premise she has set up is completely plausible for a video game and the player has no alternative explanation for the strange situation their character is in. I suspect that for a number of players, disbelieving Nowak hadn’t even occurred to them until she urged them not to. Nowak is the character who argues for faith, but “faith in the possibility of good” doesn’t necessarily translate to “believe everything said by the first stranger you meet.” So I suspect this line was actually intended to sow doubt - at this point there’s still no story but Nowak’s, but it’ll be easier to accept ambiguity later if the player doesn’t completely buy what they’re being told now. And this ambiguity is periodically reinforced by Nowak’s frequent use of the phrase “fingers crossed” - which can mean either a wish for luck or the telling of a lie.

Story Analysis: Moving Forward and Laying a Foundation

Nowak’s exposition ends and the player character is left alone. Whether or not they believe her, there’s nothing to do but move forward and solve puzzles. This remains true throughout the game in a very straightforward example of option restriction. If the player doesn’t want to quit and they want anything interesting to happen, their only choice is to progress along the game’s linear path.

After a few puzzle rooms, another radio signal kicks in. It’s a man’s voice this time, but the audio is very broken up and the only part that can be clearly made out is “nine one nine.” The transmission ends without explanation, and since the player character’s microphone isn’t working he can’t ask Nowak about it when she calls again after a few more puzzles. Here’s how she greets the player character in that transmission:

“Hello? Can you hear me? Huh, no point in saying that, is there. (sighing) Okay. I’m gonna have faith.”

Now that the player has their bearings, they’re a little more likely to pick up on what this says about Nowak. She’s in a situation where she doesn’t and in fact can’t know whether her efforts are having any effect at all. If the player character can’t hear her, it doesn’t matter whether she speaks. But if he can, then it’s very important that she does speak, to keep him going on his mission. So faith in the possibility of good requires her to assume she’s being heard and speak accordingly.

Nowak goes on to say that Mission Control is concerned because they don’t know whether the player character has lost his memory. Knowing this was a possibility, he apparently wrote a letter to himself about his life before going on the mission, since one method for treating amnesiac patients is to remind them of important events they’ve experienced. Nowak reads out some highlights from the letter - he lives in Colorado Springs but got married in Iceland and has no children - before orbiting back out of range, leaving the player alone with the puzzles.

I mentioned before that it might have seemed strange that the game commits to a male player character. This moment is when that starts to pay off. I suspect the use of male pronouns at the very beginning was mostly so that it wouldn’t be jarring in this later scene to learn some more specifics. Now that those details are being revealed, it becomes clear that the player character is intended to be a defined person with a full history. This reinforces that the game is set in a world that does have an objective truth, not one that’s ambiguous or created by the player. The player doesn’t yet have all the pieces of that truth, but they are out there and they do matter. Later, this foundation will enable the player to wonder who’s telling the truth between Nowak and Nine-One-Nine - it’s an implicit promise that it’s worth considering and weighing the evidence because there’s a consistent reality underneath.

After another indecipherable transmission from Nine-One-Nine, Nowak reads the player character more from the letter. But this time it’s not just biographic information. This time it’s something deeply personal and emotional.

“So, I want you to know, I’m only reading this because you wrote it to yourself. (deep breath) It was three PM on a Sunday. You were upstairs at home. A teenage boy broke into your house. He thought you were away on vacation. You went downstairs with your gun. You shot him in your living room. Only he wasn’t trying to rob you. He was passing by and saw a fire in your kitchen. He broke in to try and put it out. He was young and stupid and probably should have thought of a better solution. But you assumed the worst. You assumed the very worst and you shot him. He was paralyzed from the neck down. He died seven years later, alone, at night, in Penrose-St. Francis Hospital… I’m orbiting out. I hope that helped you. Fingers crossed.”

It’s a dark story, and it’s easy to see how someone who’d lived it would identify it as one of their most intense and significant memories. So it’s believable that the player character would have chosen this story to try to combat their potential amnesia. But there’s more going on here - the story is a cautionary tale about assuming the worst and hurting people who are trying to help you. The moral is very clearly not to do that.

It’s worth emphasizing here that the virtue Nowak embodies and encourages is “faith in the possibility of good” - not faith in the certainty of good. It’s not blind optimism - if Nowak were sure everything would work out, she wouldn’t bother with the letter. Instead, Nowak has faith that it can work out if she does what’s necessary. Her philosophy of pragmatic optimism allows her to face reality but ensures she will never let an important opportunity pass by or give up unnecessarily.

Similarly, the lesson of the intruder story isn’t that you should leave your gun behind. The intruder easily could be hostile, in which case the gun could be quite helpful. The lesson is that you shouldn’t fire your gun before making sure that’s the right thing to do. To protect the possibility of good, you must prepare for the worst but not assume it.

When the player character realized he had an intruder, he had a choice. He could have believed it was possible that the intruder was not a violent burglar, in which case shooting him before asking questions would be a terrible thing to do. He would have held off long enough to ascertain the truth and nobody would have been hurt. Or he could have rejected that possibility and assumed the worst, in which case shooting immediately is the right thing to do. This is what he did, and it ruined the life of an innocent.

The stakes are much higher now. The boy was trying to help save a house, and lack of faith doomed him. Nowak is trying to help save the world, and this time lack of faith would doom the whole planet.

Story Analysis: Introducing the Contrarian

Now that Nowak’s philosophy is well established, it’s time for it to be challenged. After some more puzzle-solving, Nine-One-Nine comes back on and this time you can actually make out what he says.

“You, listen! I know you can hear me down there. She’s lying to you. She’s a liar! You’re not where they say you are! They’ll leave you alone to die in the dark.”

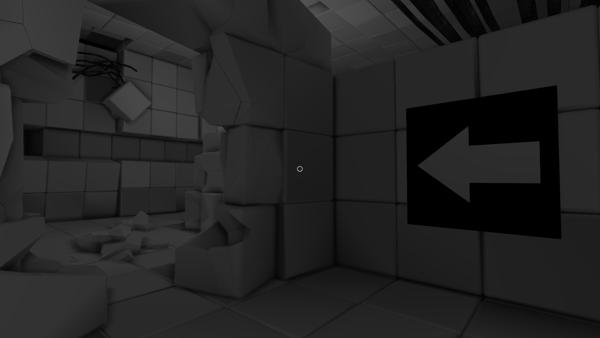

The transmission ends, and the player character is deposited in the game’s darkest area. It’s impossibly dark - there are a few lights on the walls and the cubes you can interact with are lit up, but everything else is utterly black, as though all the other surfaces absorb light rather than reflecting it.

It’s a very stark contrast, appropriate enough for Nine-One-Nine’s sudden claim that everything the player has been told so far is a lie. In fact, it’s a little too on the nose - but deliberately so, I believe. Here are the reactions to this moment in the two Let’s Plays I used as dialog references:

“So she’s a liar - are we doing that again? Come on. I quite liked when games weren’t about lying.”

—Anistuffs - The Indian Let’s Player, Let’s Play Q.U.B.E. Director’s Cut - Part 5 of 16 - That Blooming Bloom

“Oh man, I knew it. It is like Portal.”

—Quaint Hydra, Q.U.B.E. Directors Cut [Part 2]: Truth, What Is The Truth

I think this is exactly what Yescombe wants the reaction to be. The savvy player has probably already wondered whether Nowak is to be believed, especially after the small out-of-place clues like her early exhortation to believe her story and then the mysterious transmissions with a different voice. Now that Nine-One-Nine has managed to explicitly say that Nowak is lying, he also says the player character will be left alone in the dark at the exact moment the player character finds themselves alone in the dark.

It’s an unsubtle way to add weight to Nine-One-Nine’s claim, and I think that’s the point. Players may be skeptical that the game would be so lazily written as to straight-up copy Portal, but if it’s willing to use such a ham-fisted visual metaphor, maybe it really is that lazy. The savvy player is thus being loaded with the expectation that Nowak will betray them, in order to magnify the relief that will come when the game ends and it’s revealed as a double subversion that only pretends to set up that tired twist.

After a few puzzles, Nowak establishes contact again. The player can’t confront her and she hasn’t heard Nine-One-Nine herself, as he only transmits when Nowak is out of range. But now everything she says is colored by the doubt Nine-One-Nine has planted. Nowak hasn’t really backed up any of her claims and much of what the player thought they knew came only from her. In this transmission, she mostly just restates her key claims which gives the player a chance to reevaluate them: you can stop the Qube by solving its puzzles, Nowak is on the ISS and the only one who can reach you (and by implication, you are in outer space), and being “alone in the dark” is psychologically damaging. The one new piece of information is why Nowak understands how hard it is being alone in space - she’s alone too.

“I know it’s tough, being alone out there. I’ve been alone here on the International Space Station for… over a month. Going around and around and around the earth. And after a while, it messes with your head. The truth is, if you leave a person alone in the dark long enough, they’ll lose themselves.”

It’s more sympathetic and humanizing than what you’d expect to hear from a fake ally who’s just been revealed, but the player is likely to regard it with suspicion after Nine-One-Nine’s claim. It’s unclear at this point whether it’s genuine vulnerability or a falsehood designed to create sympathy and trust, but it adds some dimension to her character that will be explored later on.

Eventually the player character emerges from the darkness back into a normally-lit area. After a burst of static, Nine-One-Nine has his longest transmission yet.

“I don’t have much power left. I’ve been listening from inside my box. They say you’re out in space - you’re not. You’re underground. They’ve buried you alive down there so they can test you. They’re going to test you and test you until you rot into dust. And they do something to your memory. They did it to mine. They don’t want you to remember who you are because if you don’t know what’s happening you’ll have faith that it will end, you’ll have faith that someone will let you out of the dark, but they won’t. You have to rip that faith out of your skull and replace it with truth. Or you’ll die down there.”

Nine-One-Nine has finally presented an alternate explanation for what’s going on, and - leaning even further into the comparison and expectations that already exist in the player’s mind - his claims are straight out of Portal. The only addition is the amnesia which he claims was deliberately inflicted on you so that you wouldn’t know the truth. This still doesn’t prove the player character actually has amnesia, but lends more weight to the reading that he does. This way, after all, the character would be facing the same crucial question as the player: who is telling the truth? Whose version of reality is correct?

Story Analysis: The Ideological Conflict

Interspersed between more puzzles, the player hears from Nowak again and then Nine-One-Nine. Now that the player understands both of their claims, the conflict between them has become the focus of the story. As such, their dialog plays up that conflict even though Nowak still doesn’t know Nine-One-Nine is talking to you. Nowak tells you that the Qube is starting to come apart and that you’re getting close enough to Earth to arrange a linkup to Mission Control so you can talk to your wife. Nine-One-Nine says this:

“I haven’t got much power left, so open your ears. Doubt is like a tiny plant trying to push its way torwards the light. But as soon as she sees it poking out of the dirt, she pours on more soothing words to kill it. You’re making the Qube fall apart, you’re going to get to talk to your wife, you’re gonna get out! You’re gonna go home. You’re going to save the whole Earth. That’s her poison. And you’re drinking it! If you want it to stop, you have to stop it.”

If Nowak’s philosophy is pragmatic optimism, Nine-One-Nine’s is rebellious pessimism. It’s not just skepticism - he doesn’t invite you to evaluate Nowak’s claims, but to reject them outright lest they kill your precious doubt. Faith in the possibility of good is a tool used by your captors, and unless you abandon it you’ll never escape their trap.

Although he urges you not to believe Nowak, Nine-One-Nine doesn’t propose an alternate course of action. The implication is certainly that he doesn’t think you should be obediently solving puzzles, but what else can you do? There are no apparent escapes - the only way to move is forward, through the puzzles. The option restriction is still very much in effect. So despite the uncertainty, most players are likely to keep solving puzzles and moving forward. This means the player is free to wonder who’s telling the truth without having to decide. This lets them remain curious and engaged with the mystery instead of just waiting to find out whether they are right or wrong in their chosen answer.

Before long, the player character reaches a doorway much like several they’ve passed through before, but this time there’s a malfunction. The floor drops like an elevator with a snapped cable and the player plummets with it down, down, down, finally coming to a crashing halt somewhere deep in the Qube. There’s a lot of rubble and exposed cables where the walls are damaged or collapsed.

As they regain their balance, a radio transmission cuts in. It’s Nowak, who opens by saying “I have faith you can hear me.” She goes on to claim that the Qube is coming apart even more than before and the linkup with your wife should happen soon. That’s all the news she has, but she decides to tell you more than just news.

“But I figure talking to you is therapeutic. Especially for me, actually. What I said before - about how being alone out here can mess with you… it’s messed with me too. I can’t talk to Mission Control about it or they’d cut me short. I figure - with your radio out, you can keep a secret. (deep sigh) Fifteen days ago, I was on a spacewalk on the outside of the station. I was replacing one of the old communication antennas. The sun was disappearing over the western edge of the Earth behind me. And it gets so quiet out there, so dark. Sometimes you can’t be sure you’re there at all. I finish the job, I start to move away… and, uh… and I hear this voice. Only, it’s my voice. Not in my mouth, not in my head, but outside, next to my ear. It’s the only way I can explain it. And the voice, it said… it said… (labored breath) ‘God is dead.’ (coughing, sniffling) And it scared the hell out of me. (sniffle) I grabbed my tether and pulled myself back into the airlock and shut the door. (sigh) I know it’s just my brain keeping itself busy. (sniffle) And that’s why we do isolation tests before we go out - but, Christ. I’m orbiting out of range. I’m sorry. Keep going. Please keep going.”

It’s the payoff of Nowak’s earlier hint of vulnerability. She tells you her secret, the event that shook her hard and that she hasn’t been able to share with anyone else. It doesn’t seem like something a captor would say to motivate a prisoner to solve puzzles and it’s hard not to be convinced by its apparently sincere emotional depth. In a way, it’s the strongest piece of evidence yet that Nowak is actually telling you the truth.

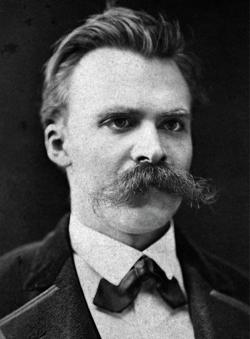

But it’s a lot more than that. “God is dead” is a chilling thing to hear from a disembodied voice alone in space, but it’s also a perfect encapsulation of the dilemma at the core of the game’s conflict. To explain why, we’re going to have to take a moment to talk about Nietzsche.

Sidebar: God is Dead

For Nietzsche, “God is dead” was a social statement, not a religious one. It wasn’t about the literal death of a deity, but rather an observation on the waning influence of the Christian church in post-Enlightenment Europe. God was “dead” in that the lives of individuals and the progress of society were increasingly understood to be directed by natural processes rather than divine destiny. But in a culture that had been built with the church at its center, this meant many important questions no longer had easy answers. How should people live, if they no longer have the word of God to follow? Without divine decree, how can we know what’s right or wrong? Is there any such thing?

“God is dead” is shorthand for a society-level existential crisis. An entire people had the foundations of their morality and worldview ripped out from under them, and it was not at all obvious how to rebuild. One option was to remain in denial, accepting the prominence of scientific knowledge while pretending this didn’t remove all justification for traditional frameworks of ethics and values. This could be quite tempting, as dismissing those frameworks would open the door to nihilism - the conclusion that our existence and experiences are fundamentally meaningless.

But in Nietzsche’s analysis, if humanity was strong enough it could rise to the incredible opportunity of building a new foundation to life - a truer and stronger one that would allow us to reach far greater heights. Nietzsche saw this as a necessary step in the evolution of a culture: we must face the realization that there’s nothing out there and decide how to react. Do we close our eyes and cling to outdated views of universal good and evil? Or do we confront the emptiness and do the hard work of building our own value system anew?

Nowak and Nine-One-Nine have both had their “God is dead” moments and they reacted differently. Q.U.B.E: Director’s Cut is the story of the conflict between their philosophies as expressed through their attempts to persuade the player character to follow their way of thinking.

Nine-One-Nine’s moment came seven years ago. As we later find out, he’s an astronaut whose shuttle malfunctioned and lost contact with Earth. While we never learn the details, I think this is intended to be read as an unpredictable tragedy, no more complicated than it sounds. Nine-One-Nine suffered a terrible fate and found himself alone in the dark through no fault of his own and not due to any greater plan. A bad thing happened to a good person, and it didn’t mean anything.

We don’t know how Nine-One-Nine reacted to this at first, but by the time of the game he’s found a way to internalize it. Unfortunately, he hasn’t been able to confront and overcome the nihilistic implications of his experience. Instead, he clings to outdated and inaccurate moral interpretations. For the universe to still be a place where things happen for a reason, Nine-One-Nine’s fate must have been due to a planned and deliberate act - an evil act. He isn’t just a victim of circumstance - he’s a prisoner, and that means he has captors. This view may well have kept him alive by justifying his suffering and giving him someone to fight - but it means that when he hears Nowak give an incompatible explanation, he assumes she’s one of his captors and is ready to fight her. If the player listened to him and stopped solving puzzles, not only would Nine-One-Nine’s failure to confront and overcome nihilism have destroyed his only chance to finally be rescued, but it actually would have doomed the entire world.

Nowak’s moment came fifteen days ago. The Qube was just a couple weeks away from wiping out all human life. The world’s last hope was an astronaut sent out to the Qube alone in a desperate attempt to stop it. And he’d just lost consciousness and possibly died.

Unlike Nine-One-Nine, Nowak knew what this meant: nothing. It was her own voice that told her that God was dead. It terrified her, but she confronted and overcame it. Because she knew God was dead, she knew that there was no divinely ordained reason for the mission to fail and the world to end. It wasn’t happening on purpose or as part of some grand design. Mission Control gave up and accepted their fate, but Nowak knew there was no such thing as a fate to accept. She kept faith in the possibility of good and continued to do whatever she could, transmitting to the player character in case he could hear her, and as a result the world was saved.

Nietzsche and Yescombe both teach us: you can’t fight the dark if you accept it as part of the plan. You can’t save the world without killing God.

Story Analysis: Confrontation

Okay, back to the game. Having fallen into a damaged portion of the Qube, the player character finds a path forward through the wreckage solving several puzzles that involve manipulating live wires to restore power to cubes so they can be used to proceed - and after that, breaking holes in walls to create new paths. Eventually, Nine-One-Nine speaks again.

“Listen to me. The whole thing is bullshit. I can see on your camera - look around you. You really think this is an alien craft? The colors, symbols - they’re all human! They’re all things you can understand and solve. It’s all part of it. And you think the Qube is really falling to pieces? The hanging wires, the holes in the wall - none of them lead you anywhere they don’t want you to go.”

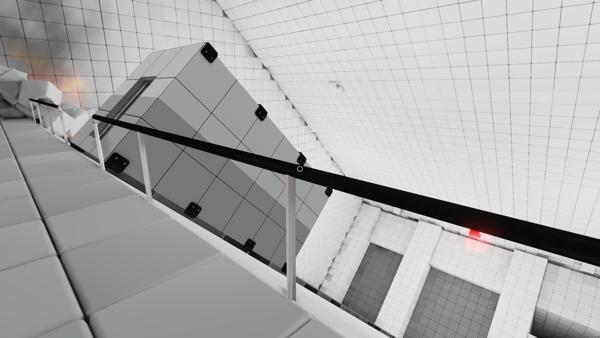

It’s Nine-One-Nine’s most damning argument, and it’s immediately reinforced by a huge arrow sign pointing you through a hole in a damaged wall. It’s a clear reminder that every part of the Qube’s design, including the apparent damage, is completely intentional and completely readable. This makes a lot more sense if it’s a series of human-designed test chambers - which was the setting in Portal - than a genuine alien craft.

Players - especially savvy ones who have internalized the language of video games - may not have consciously considered the way they’ve been shepherded along so far. It’s just part of the assumption of game and level design that the player will be steered toward content and progression. Calling attention to it in this way works as an in-universe argument against Nowak, but also - like the sudden arrival in the dark area before - as a signal to the player. This time, it suggests that deconstruction is afoot and their standard assumptions are not safe. But this, too, has been done before, so it’s likely to further persuade the player that a familiar twist is coming.

The game does eventually reveal that you actually are in an alien craft, but does not counter or justify Nine-One-Nine’s point. Maybe there’s an explanation in Q.U.B.E. 2, but there isn’t one here. The consistent readability of the Qube, the fact that there’s always one path forward, and the fact that you destroy it by solving puzzles are left as an open mystery, and to the player they may seem to just be consequences of the fact that you are playing a video game. Nine-One-Nine’s point can thus come across as a bit of a lampshade hanging, which is unfortunate as it implies that the creators didn’t find a good way to fully integrate story and game design. But in the moment, it’s still a well-placed escalation of the argument between Nowak and Nine-One-Nine - her last transmission about her “God is dead” moment was her most convincing one yet, and now Nine-One-Nine has given his.

But he still doesn’t offer an alternative besides telling you to “lose your faith.” That’s not a course of action. Nine-One-Nine’s philosophy is fundamentally empty. Because it refuses to acknowledge its own emptiness, it cannot overcome it. If Nowak’s telling the truth, then it’s very important that the player character do as she says. If Nine-One-Nine is telling the truth, then it doesn’t matter what the player character does.

So, the player keeps going. And after several more puzzles, Nowak speaks. She tells the player character that (as Nine-One-Nine predicted) the promised linkup with his wife won’t be happening. She also mentions that she’s noticed some “interference on [his] signal frequency” but it’s probably nothing - the player, of course, is likely to recognize that it’s Nine-One-Nine. After a few more puzzles, he’s back - but this time, Nowak’s in range and can hear him. Now that they’ve each made their strongest arguments, it’s time for them to clash directly.

NINE-ONE-NINE: “You heard it in her voice, didn’t you? Her lies catching in her throat. Did you really believe that the fate of the planet depends on you solving puzzles in a box? They lie to give you just enough hope to keep you where they want you: alone, in the dark. Just you, and the voices in your head.”

NOWAK: “Hello? Who is this? Who are you and how are you on this frequency? Sir, this is a private government channel. I don’t know how you’re broadcasting out here but what you’re doing is illegal. What is your name?”

NINE-ONE-NINE: “You people scrubbed my name out of my head! All I am is a number you gave me. Nine one nine. And you can pretend all you want but now he knows the truth - no faith, just facts!”

NOWAK: “Hello? Hello? Listen to me: I have no idea who that person is. Whatever he’s been saying to you, you need to ignore it. If he contacts you again, just blank it out. I’ll contact Mission Control and find out what the hell is going on. I’m orbiting out of range, but remember: your mission is everything. The entire world is depending on you.”

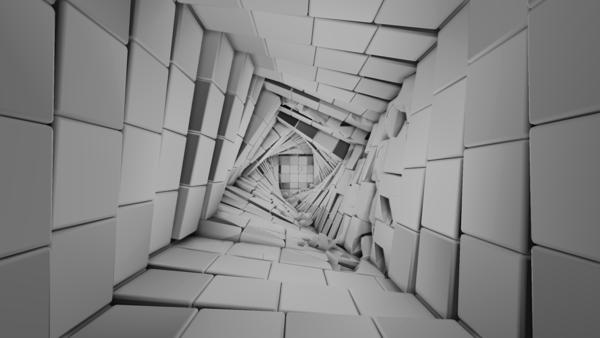

They’ve each reiterated their core claims, but no new evidence is on offer. There is still no option but to proceed through a new area of the Qube which is less damaged but more surreal with corridors that pulse and rotate. It’s another visual metaphor for the player’s condition - tension is ramping up and there’s no solid foundation for knowing what to believe.

After a handful of puzzles, Nowak is back in range, and tells you who Nine-One-Nine is.

“Mission Control say that seven years ago, they had a space shuttle malfunction and fall out of orbit. The shuttle’s name was nine one nine. They lost contact, it drifted out into deep space, and everyone assumed the astronaut on board was dead. It’s possible that his suit kept him alive. . . . The astronaut’s name was Jonathan Burns. And if he is Jonathan Burns, he’s been alone in the dark for a very, very long time.”

Naturally, Nine-One-Nine denies this, proffering his own explanation.

“She’s lying! (sniff) That’s how people lie: with lots of little details. They tell you about a date, a time, a name - it makes it seem real, but it’s not real. . . . The name they told you, Jonathan Burns - it’s not a name, it’s a threat. You’re Jonathan, and they’re going to burn you! Jesus Christ, they’re going to make you walk right into the incinerator!”

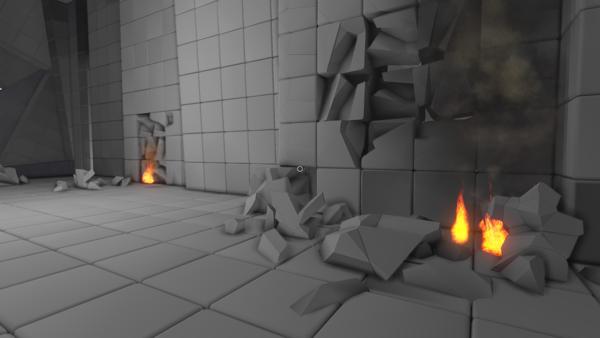

As happened before with the dark area and the arrow sign, the environment punctuates Nine-One-Nine’s message in a literal way: the player character reaches a new area where there are actually small fires burning in some of the damaged spots.

As before, this seems engineered to remind the player of Portal. In that game, GLaDOS intended to trick the player character into a fiery death, and only quick thinking and a clever application of the portal gun allow her to escape. After all the other parallels so far, and with another helping of deliberately unsubtle foreshadowing, it’s easy to believe Nowak may be about to attempt the same thing.

Story Analysis: Suicide or Salvation

Shortly thereafter, the player enters a large chamber that has a few objects that might be escape shuttles. They’re roughly van-sized with human-sized doors and are on slanted tracks leading down somewhere the player can’t see.

When approached, the doors open to reveal lights, machinery, and what appears to be a control console. Nowak urges the player character to get in and escape the collapsing Qube while Nine-One-Nine urges him not to.

NOWAK: “Oh god - you need get out of there right now! The whole thing is co- the whole thing is coming apart! There’s an escape shuttle dead ahead - get in and go!”

NINE-ONE-NINE: “No! It’s not a shuttle! It’s a coffin! And they want you to launch yourself into the incinerator! You knew the second you woke up here - I know you knew it! Her fingers are crossed behind her back!”

NOWAK: “Go! Don’t listen to him; he’s crazy, he’s lying, I don’t know; get in the shuttle!”

NINE-ONE-NINE: “They’re trying to jam my signal - don’t listen to her!”

NOWAK: “Please, I-I don’t want you to die!”

NINE-ONE-NINE: “That’s the only thing they want!”

NOWAK: “I’m moving out of range - please, go!”

NINE-ONE-NINE: “Do you think it’s a coincidence there are no windows to prove you’re in outer space? They already buried you; don’t kill yourself for them too!”

It’s the moment when the player is finally called upon to choose who to believe. But the deck is still stacked. If Nowak is telling the truth, then the player character needs to get in the shuttle or he’ll die. If Nine-One-Nine’s telling the truth, the player character is likely dead no matter what he does, and Nine-One-Nine still hasn’t provided an alternative. It’s possible to cut off their shouting match as early as Nine-One-Nine’s first objection by just getting in the shuttle, but even if the player just stands around waiting, nothing really happens. There’s smoke and fire and audible explosions in the distance that shake the area, but that’s it until the player character gets into the shuttle. In the end, the player has no choice but to do as Nowak says.

Upon entering the shuttle, the final cutscene starts. The player character sits at the controls and presses the launch button.

NOWAK: “Keep going - you’re a hero! The President is on the line waiting to talk to you!”

NINE-ONE-NINE: “The President’s not down there! No one’s down there! No - no! What the hell are you doing? Stop it! Get out! For God’s sake, get out!”

The shuttle races down a tunnel, faster and faster, as Nowak and Nine-One-Nine keep shouting.

NOWAK: “We’re all waiting for you, everyone’s waiting for you! The whole planet, your wife’s there - your entire life is waiting for you at the end!”

NINE-ONE-NINE: “This is the end! They’re gonna burn you alive - you can still stop it, rip out the wires! Smash out the buttons! Please, don’t leave me! Please don’t leave me. Don’t leave.”

The shuttle emerges into space, Nine-One-Nine’s final plaintive request not to be left alone again hanging in the air. Scattered Qube fragments can be seen, and beyond them - Earth.

The player is allowed a few moments to soak it in, and as the shuttle slowly turns to reveal the entire Qube coming apart, new voices are heard - from Earth.

MISSION CONTROL: “This is Mission Control. Damn, it’s good to see you. (cheers and applause in background) We have someone special on the line for you.”

WIFE: “It’s me. Oh my gosh; you’re okay! I knew you you would do it, I-I knew you would, but… (sigh) Just come home now, okay? Please, just come home. Here’s something I-I never thought I’d say: the President wants to talk to you.”

MISSION CONTROL: “Go ahead, sir.”

PRESIDENT: “Well, ’thank you’ just doesn’t quite cut it, does it? You haven’t just saved the lives of every person on this planet; you found a life we thought was lost forever: Captain Jonathan Burns of Shuttle Nine One Nine. And Captain Burns - now we know you’re out there, we will not rest until we bring you home, no matter what. I assure you - you are found. As for you, you may have had your doubts through all this but you persevered. In life, we don’t get proof until it’s done. That’s how humanity achieves great things. By having faith in the possibility of good.”

Roll credits.

Beyond the Story: A Happy Ending

At the moment when I saw the Earth and the stars, I was relieved. Very, very relieved. I was surprised how relieved I was. And I wasn’t the only one.

“It’s not just the novelty of a triumphant ending – They’re not as common as I’d like but they’re certainly not rare – nor is it the novelty of being surprised, as I’ve been slapped in the face with any amount of random baloney in my life. It’s more the combination: being pleasantly surprised by a happy ending.

Pleasant surprises are, shall we say, uncommon. . . . So at the end of Q.U.B.E. I realized I had been holding my breath waiting for the other shoe that would surely drop on my head. . . . There was no shoe. …I was astonished, bewildered and elated in turn. Here was this elaborate puzzle game, steeped in science-fiction tropes, and they ended it hopefully, even happily? Is that even allowed?

Well, yes, as it turns out. Sometimes that happens. Sometimes you can spend hours dreading something, only to find out that your dread was misplaced. . . . It’s nice, on occasion, to have the good presented to you on a plate instead of having to go digging for it. It’s a reminder that, even in the imagination of a science fiction writer, sometimes things can work out just fine.”

—Greg Decker, The Twist

Every part of the story of Q.U.B.E: Director’s Cut builds to this moment. All of Nowak’s and Nine-One-Nine’s dialog, the drop into darkness, the arrow sign on the wall, the fires, forcing you into the escape shuttle before you can be sure that’s what it is, Nowak and Nine-One-Nine shouting against each other until the very last moment of uncertainty. Everything is set up to create apprehension that you’re being lead into a trap - especially if you’ve played Portal or other games that do the same thing - and crescendo it to maximum right before the reveal.

So when the reveal is that Nowak is trustworthy and it’s not a trap - and by implication, that you’ve just saved your own life and the entire world - the impact can be intense.

Q.U.B.E: Director’s Cut does force players into a particular ending, but instead of a dark, pointless, and cynical one, it’s a triumphant, uplifting, and optimistic one. Other games require the player to do as their supposed ally says and then burn them for it whether or not they see through the deception, and it’s always frustrating to be berated for the unavoidable actions of your character. Q.U.B.E: Director’s Cut requires the player to do as their supposed ally says and then rewards them for it. The player might have believed Nine-One-Nine, but if so they never really had the chance to act on it. The player isn’t supposed to feel bad that they didn’t trust Nowak - they player is supposed to feel good that they had faith in the possibility of good. And so the game ends with the President delivering the moral of the story with those same words that Nowak used at the very beginning.

But I think there’s still a bit more going on here. This story isn’t just a reaction to Portal. It’s not just about having a game surprise you with a happy ending. Recall what Yescombe said about it (emphasis mine):

“We are conditioned to expect death and doom. We’re resigned to it. At its heart, this story is about that state of mind and how it effects the way we view our experiences, in games and in life.”

Most of us haven’t been trapped alone in space for seven years, but have had bad things happen to us that we didn’t deserve. Most of us aren’t at risk of disrupting a mission to save the planet, but do interact with people who are trying to be more constructive and productive than we are. We can react like Nine-One-Nine - concluding that our misfortune is the result of evil people or organizations working against us and discouraging others from participating in their system. Or we can react like Nowak - concluding that the universe has only the worth we put into it, believing that good is possible but by no means guaranteed, and working hard to bring it about.

Nine-One-Nine’s philosophy is just a rejection - it doesn’t provide any way to fix problems or make the world better. The game shows this by not providing any sort of alternative option if the player believes him. What is such a player supposed to do? Just… stop playing? Stop moving forward, stop solving puzzles, sit outside the escape shuttle forever? How pointless and uninteresting.

But despite the fact that Nine-One-Nine has spent the entire game trying to prevent the player character from saving Earth, the game goes out of its way to make sure you know he’s not a villain and that he gets a happy ending too. The President emphasizes that Nine-One-Nine isn’t alone anymore and that he will finally get to come home. He gets rescued in spite of his philosophy. Someone with the same ideas of good and evil as Nine-One-Nine would read him as evil and deserving of punishment. But in the end, there’s no such thing as evil. We aren’t meant to hate Nine-One-Nine. He’s been through hell and who knows what we would have done under the same circumstances?

The Nine-One-Nines in our lives deserve to be saved just as much as the Nowaks, but we need Nowak’s philosophy in order to do it. It’s a more difficult way to look at the world than Nine-One-Nine’s, but far more rewarding. It acknowledges the darkness and assumes responsibility for improving it. And while the game’s final reveal shows that Nowak was right about you being in space, it also shows that she was right about how to live. Cynicism is empty and self-defeating. Faith in the possibility of good is the only thing that can save us.

It’s the only way we can save each other.

Postscript: Interview with Rob Yescombe

I reached out to Rob Yescombe while working on this essay and he graciously provided some additional context around key story elements and choices. Here’s what I asked him and how he responded:

DOCPROF: How much freedom did you have when putting the story together for the Director’s Cut? Was it clear in advance that your tools would mostly be limited to voiceover? How did the constraints affect the story you could tell?

YESCOMBE: In the reviews for the original Q.U.B.E., one of the most common criticisms was the lack of a story. So when it came time to port it to console, the team wanted to add one – and very kindly asked me to do it. The problem was they had no scope to add any new content besides extending a few corridors. For me then, the challenge was to figure out a way to tell a story that felt like it belonged in a finished game that was never intended to have one – and do the entire thing with just audio, because that was the cheapest method.

So whilst the team gave me creative freedom, the actual practical constraints were extraordinarily tight. We couldn’t afford a big cast, so I concluded a “two hander” thriller would be the best story structure to use.

DOCPROF: It’s very easy to read the story as a response to Portal, deliberately leading players to expect a similar plot and then surprising them with a happy ending. Was this your intent? Were there any other specific games or stories you had in mind?

YESCOMBE: Exactly right – another criticism in reviews for the original Q.U.B.E. was that the game looked so much like Portal. I realised this similarity set a very particular expectation for any story I might write for the Director’s Cut. So rather than running away from that, I decided to use people’s knowledge of Portal as plot device; to address the original criticism by turning it into a twist in the story.

DOCPROF: “Faith in the possibility of good” is one of the first things the player hears and the very last thing said to them. It seems to be a very deliberate wording - what is the origin of this phrase? Why did you decide to use it instead of just saying “hope” or similar?

YESCOMBE: That phrase is the message of the story: don’t assume the worst. It could be stated in a more familiar way, but a line of dialogue that is a little off-kilter is easier for people to retain over the course of a whole game. I grew up watching David Mamet – the master of the off-kilter line. So this was perhaps my hack attempt at that.

DOCPROF: Nine-One-Nine makes the point that there’s no reason an alien spacecraft should be human-readable and present a path of puzzles that destroy it when solved, which may be his strongest evidence that Nowak is lying. I didn’t find an explanation for this in-game - did you have one in mind?

YESCOMBE: There’s a great line Richard Hatem wrote in The Mothman Prophecies: “These entities are more advanced than us, so why don’t they just come right out and tell us what’s on their mind? Well, you’re more advanced than a cockroach, but have you ever tried explaining yourself to one?” The assumption that we can ask the heavens a question and be capable of understanding the answer is mankind’s most profound arrogance.

DOCPROF: What lead you to “God is dead” for Nowak’s hallucination? You’re quoted as saying the Director’s Cut story is about being “conditioned to expect death and doom” - were you already considering this through a Nietzschean frame, or did that come up while writing the story?

YESCOMBE: Because conflict is the heart of drama, good things in stories have to find a way to go badly. Through games, movies, books and TV that formula has slowly conditioned us to expect the worst when things look good. The voice Nowak hears is her own. It’s her own doubt in something she deems to be good. Her state of mind, like Nine-One-Nine, reflects the inner monologue of the player.

DOCPROF: Are there any specific individuals or groups, real or fictional, that Nowak or Nine-One-Nine were inspired by?

YESCOMBE: No. They’re both just structural devices to deliver the narrative – and behind the mystery of who’s telling you the truth, the story is really about how you, the player, feel about stories. Some players were very surprised by the ending, and others weren’t surprised at all, which is a direct result of how much personal faith they may or may not have in the possibility of a good outcome.