Play Me A Story, Part One: Metal Gear Solid and the Cinematic Game

Recently I’ve been watching my friend Iceman play through the Metal Gear Solid games. It’s been both entertaining and edifying. My own much-delayed foray into the series ended shortly after tossing grenades into a tank in the first game, and it seems that for every hour I watch Iceman play, I suddenly understand another previously-baffling joke or reference I’ve encountered somewhere.

As we watched the credits roll on the third installment, Snake Eater, Iceman turned to me and sadly confessed that he was starting to doubt the ability of video games, as a medium, to tell stories.

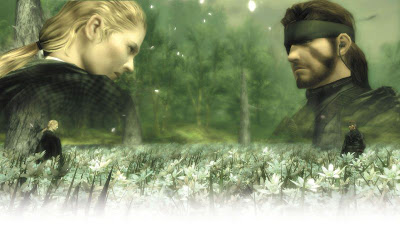

It’s a surprising thing to hear after watching the video game ending that holds the record for producing manly tears. But I knew exactly what he meant, and why he’d said it.

This can only end one way: THE MANLIEST OF TEARS.

The Metal Gear Solid series is known for a lot of things. One is the fact that the ratio of cutscene-to-gameplay increases markedly with each installment. In the first game, cutscenes are mostly limited to the intro and ending, and scenes bookending each boss fight. The fourth and latest game, Guns of the Patriots, has roughly eight hours of cutscenes. Part of this is down to technology - the first Metal Gear Solid was on the original PlayStation, and featured character models with no ability to change facial expression. Consequently, much of the exposition was delivered via the decidedly un-cinematic method of CODEC conversations - the in-game two-way-radio, which displayed two character portraits (which could actually open their mouths) conversing over a black background. As graphics have improved, Metal Gear Solid has relied increasingly on fully-rendered cutscenes instead.

The odd result, however, is that exposition in the later games is more jarring to the player. We’re used to not controlling conversation. When we just see the player character talking to someone else, that doesn’t feel wrong. But if we see that character doing things we’d normally be in charge of - fighting, maneuvering, sneaking, exploring - it breaks us out of the immersion. Our game has been replaced by a movie. Suddenly we are no longer Snake. Instead, we are simply watching him.

These moments are certainly cinematic - a word often used to favorably describe accomplished video game storytelling. But why should this word be such a compliment? Whenever I see an article like 15 Most Cinematic Gaming Moments, I have to shake my head. Would anyone compile a list of the 15 Most Cinematic Moments in Books? Or the 15 Most Literary Moments in Interpretive Dance?

The implication that the best storytelling to which video games can aspire is cinematic is as limiting as it is misguided. When a new medium arises, it is inevitably compared to whatever it superficially resembles, and indeed that is where it takes its early cues. Early film was little more than recorded stage productions. Comics are still popularly regarded as illustrated books.

But given time and artistic progress, each medium comes into its own. Creators stop relying on inherited tropes and begin using the medium’s own power. Mature media rarely imitate each other, and there is good reason for this: techniques that play to the strengths of one medium rarely play to the strengths of another.

“Have you noticed that in films there are lots of car chases? There are no car chases in books, are there? ‘He looked up in the mirror. Behind him, the man was driving. He looked in the mirror and then he was driving. Oh, they drove faster, faster, driving fast and looking in the mirror. The other guy was pulling a face and driving fast, and then there was a terrible crash.’ Just doesn’t fucking work, does it? Anyway…"

—Eddie Izzard, Unrepeatable

So what, then, are the narrative strengths of video games? Interactivity and dynamism. Video games are the medium most capable of telling stories about the audience, by virtue of the fact that the audience is a central, active participant in the storytelling.

Other media have flirted with this. I adored the Choose Your Own Adventure gamebooks as a child, and I’ve seen my share of mystery dinners and similar plays. But the books simply shunt the reader down one of a handful of pre-written, identical-every-time tracks. The plays are about their own characters, due to the limits of needing to interact with a large audience rather than a single individual. Video games do not always rise above these limitations. But unlike other media, they can.

It’s a scary idea, however. Interactivity means ceding a degree of control to the player. It means the creator no longer has a guarantee of exactly how the work will be experienced. Hideo Kojima, the creator of Metal Gear Solid, is very much aware of this.

“Storytelling is very difficult. But adding the flavour helps to relay the storytelling, meaning in a cut scene, with a set camera and effects, you can make the users feel sorrow, or make them happy or laugh. This is an easy approach, which we have been doing. That is one point, the second point is that if I make multiple storylines and allow the users to select which story, this might really sacrifice the deep emotion the user might feel; when there’s a concrete storyline, and you kind of go along that rail, you feel the destiny of the story, which at the end, makes you feel more moved. But when you make it interactive - if you want multiple stories where you go one way or another - will that make the player more moved when he or she finishes the game? These two points are really the key which I am thinking about, and if this works, I think I could probably introduce a more interactive storytelling method."

—Hideo Kojima, The Kikizo Interview 2008

“Wow, Hideo Kojima’s really scared that letting you play is gonna mess up his movie."

—Unskippable, Metal Gear Solid 4: Part 4, Metal Gear August

Kojima knows he’s cutting off player control, and he isn’t completely unapologetic about it. In the second Metal Gear Solid game, Sons of Liberty, the following lines are uttered to the player character, but may as well be spoken by Kojima directly to the actual player:

“I know you didn’t have much in terms of choices this time. But everything you felt, thought about during this mission, is yours, and what you decide to do with them is your choice.”

It’s true, of course, but the same thing is true of every medium: your reactions to it are your own. It’s not a depth inherent to the medium, but rather to the human mind. And acknowledging or even addressing the player (which Metal Gear Solid often does) is not the same as making the story about the player.

Sometimes, though, Metal Gear Solid does take that extra step and bring the player to center stage. These moments take advantage of the strengths of the medium, and tell stories in ways that only video games can. And the results are some of the most memorable sequences in the franchise, and possibly in modern gaming altogether.

They are so memorable, in fact, that I am about to spoil one of the best ones in order to illustrate my point. Read no further if you want to avoid a small-to-midsized spoiler for Snake Eater. Come back next week, when I’ll be more deeply examining the metanarrative power inherent to the medium by discussing some games that more thoroughly embrace it. (Alternately, you can find a more detailed and spoileriffic examination of the following example here.)

It’s a hallmark of the Metal Gear Solid series that there are a variety of ways to deal with the non-boss enemies. Most can be carefully sneaked past, if the player is patient enough. They can also be snuck up on from behind, and either knocked out or quietly killed. They can be shot with tranquilizer rounds, or standard bullets, or explosives.

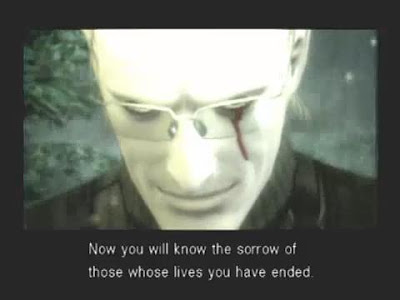

Late in Snake Eater, Snake is confronted by a powerful spirit medium known as The Sorrow. Unlike the game’s other bosses, The Sorrow does not fight Snake directly. Instead, The Sorrow forces Snake to wade down a river, swarming with the ghosts of everyone Snake has killed in the course of the game. The previously-dispatched bosses are all there, as are any and all non-boss enemies that were killed instead of disabled. What’s more, each ghost reflects his manner of death: he may have a slit throat spewing blood, or a head twisted backward due to a snapped neck, or prominent bullet holes in the body parts in which he was shot.

Snake didn’t decide to eliminate these enemies in these ways. The player orchestrated every one of these deaths. The Sorrow isn’t confronting Snake with the men Snake has murdered - he’s confronting the player with the men the player has murdered.

Snake didn't kill these men. You did. Snake was merely your weapon.

Excepting the handful of bosses, none of these deaths were necessary. The player chose these kills, probably without much thought or concern. It’s a video game, after all - enemies exist to be defeated and forgotten. But The Sorrow won’t let them stay forgotten. The sudden and unrelenting parade of the consequences of the player’s actions makes them real and horrible. This part of the story, at least, is not about how the player feels about what Snake has done. It’s about how the player feels about what the player has done. It’s almost unspeakably chilling, and it couldn’t be done in anything other than a video game.

But this is just one moment out of many. Snake reaches the end of the river, and before long it’s back to the cutscenes.

As Iceman dispatched Snake Eater’s final boss, he warned me that if I had to use the bathroom, now would be a good time, because the ending was a cutscene some thirty minutes long. When I got back, he put down the controller, and we watched the ending. It was just as epic as had been promised - full of shocking twists and tragic reveals. It was fresh off the heels of this highly cinematic sequence that Iceman voiced his doubts about video games and storytelling. I hope I was able to reassure him.

It is, after all, easy to question the narrative power of any medium that has not yet outgrown its predecessors' shadows, when all it seems to do is mimic. But media grow up. We are now in the midst of the adolescence of video games, as they seek out their own identity. It’s a promising one, as even Hideo Kojima has shown us in glimpses. And so calling a game cinematic in its storytelling isn’t a compliment, and saying that it tells its story like a video game isn’t an insult.

Click here for Part Two, which examines just what it means to tell a story like a video game.