I Told Him to Do That: Option Restriction, Choice, and Agency in Bioshock

Have you ever trapped a spider under a glass? Maybe you saw one on your kitchen floor and decided to humanely release it outdoors. So you took a drinking glass and put it down over the spider. Then perhaps you took a sheet of paper and laid it on the floor. As the spider scurried about in its prison, you gradually slid the glass onto the paper, which you could now pick up and take outside.

By doing this, you managed to move the spider where you wanted it to go - all without touching it or influencing it directly. As the spider aimlessly explored its limited circle of freedom, you advanced the walls, closing off space behind it and opening up space in front of it, in the direction you had selected. By choosing to move at all, the spider chose to move onto the paper - to the goal that you had chosen, and of which the spider was not even aware.

This is exactly how many video games work.

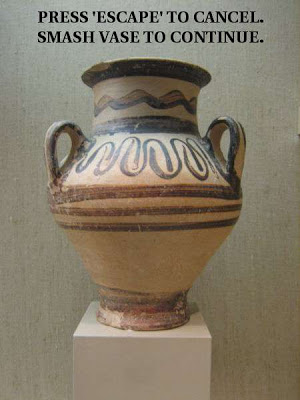

Suppose you are playing a video game that has placed your character in a locked room. To get out, you need the key - but the key has been dropped into a priceless vase on a display pedestal. You can’t reach in to get the key, and the vase is too heavy to manipulate without dropping. The only way to retrieve the key and open the door is to push the vase off the pedestal, causing it to fall to the floor and shatter.

After poking around the room for several minutes, you satisfy yourself that there is really no alternative and nothing else to do. To progress in the game, you must break the vase.

So, you do. You smash it on the ground and retrieve the key, unlocking the door and exiting the room. Whereupon an angry curator immediately berates you for destroying a priceless relic.

To what extent can you be said to have chosen to break the vase?

Your character is in a situation with only one way out. Two options present themselves: remain in the situation indefinitely, or resolve it in the only manner available. You the player have an additional option: simply reject the situation by quitting the game.

These options are all technically valid. Nothing forces you to cause your character to break the vase, and you can wait as long as you like before doing so. You retain agency, as the vase only breaks when you actively decide to break it.

But it’s a little like Henry Ford’s famous quip about the Model T: “Any customer can have a car painted any colour that he wants so long as it is black.” The relevant decision isn’t really whether to smash the vase. It’s whether to progress in the game. Any player can advance any way desired so long as that way is smashing the vase. Essentially, there is a “Press To Continue” button, which just happens to be in the shape of a smashed vase.

This sort of design is common enough that games which avoid it are a genre to themselves. Sandbox games are notable in that they don’t, as a rule, restrict your options to oblige you to proceed in a certain direction. In other games, it’s par for the course. No one really expects to be able to have Master Chief put down his gun and go vacuum his apartment, any more than we expect cop shows to feature the officers quietly doing their paperwork. It’s perfectly legitimate to constrain the player’s universe to what is fun or narratively interesting.

When you guided the spider onto the paper, you did it for the spider’s own good. In video games, option restriction serves as a direct opposite of option paralysis, which is defined as “The tendency, when given unlimited choices, to make none.” By limiting player choice to a single path, the game shepherds the player forward - hopefully, to somewhere the player will have fun.

So. Option restriction directs narrative progression by reducing player choice while maintaining player agency. Done well, it leads the player in a specific direction without removing their sense of control.

With all this in mind… wait. I should warn you. If you don’t want any spoilers for Bioshock, then I’m afraid you should read no further. Think about how option restriction is applied in other games you’ve played and come back next week. Because now, with all this in mind, I’m going to take a close look at how option restriction is used and misused in Bioshock.

WARNING: HERE THERE BE LIGHT SPOILERS

Bioshock’s story progression follows a common structure: a series of areas of relative freedom, punctuated by narrative choke points into which the player is funneled. The game does not, generally, force the player to take specific actions. But it does use option restriction quite often.

The game opens with a brief cutscene on board an airplane, which immediately crashes into the Atlantic ocean. Before ninety seconds have passed, control is handed to the player, in the water amongst the wreckage. Jack, the player character, can swim freely, but the only interesting place to go is the nearby lighthouse, as other paths dead-end in flame and debris. Once in the lighthouse, the door closes, locking Jack inside. Once more he can explore freely, but the only thing to do is enter the bathysphere at the bottom and pull the lever. Everything else is a dead end.

The next few minutes, featuring the bathysphere’s descent into Rapture, are noninteractive. The cutscene serves as an atmospheric introduction to the game’s setting.

Yet this second cutscene doesn’t feel like the first, thanks to the brief period of interactivity before it. Through option restriction, the player had no real choice, but did have agency - the player actively hit a button to pull the bathysphere lever and trigger its descent. The player brought the scene on themselves - and thus is far more engaged than they would be had the swimming and lighthouse portions been done as a cutscene as well.

Once emerging into Rapture, things get a bit more interesting. The regions in which Jack may roam grow in size and complexity, and contain increasing numbers of interactive entities - enemies, electronics, containers, etc. Jack is contacted via radio by a man called Atlas, who provides advice and goals. And the narrative choke points keep coming. Sometimes Jack needs to acquire a new ability or tool. Sometimes he needs a key or code to unlock a door. Sometimes, he needs to kill.

WARNING: HERE THERE BE MEDIUM SPOILERS

When Jack reaches an area called Fort Frolic, his contact with Atlas is cut off. Fort Frolic is presided over by a man named Sander Cohen, who somehow has the ability to block Atlas’s radio transmissions. He also cuts off Jack’s access to the bathysphere connecting to the next area. The player clearly cannot proceed unless allowed to do so by Cohen. Throughout the player’s time in Fort Frolic, goals are provided by Cohen rather than Atlas.

Cohen, it rapidly becomes clear, is one sick puppy. In cold blood, he murders a man named Fitzpatrick right in front of Jack and tells him to photograph the corpse.

However uncomfortable the player may be with this, there is again no choice, thanks to option restriction. The area in which Jack may now roam is larger than the lighthouse, but photographing Fitzpatrick’s body is just as vital to proceeding as pulling the bathysphere lever at the start. The other paths may be longer this time, but they are still dead ends.

Then, it gets worse. Cohen wants Jack to kill three more men and photograph their bodies. He opens up Jack’s access to the three areas where these men can be found, and there are no other interesting places for the player to go.

When approached, each of the men attack. This might make the player feel better about killing them - as it has become self-defense - but of course the targeted men realize Cohen has sent Jack to kill them, and are merely defending themselves as well. As is usual with option restriction, the player retains agency, playing through the combat just like the game’s other fights. But these three kills are the strangest, most horrible acts the player must commit. Unlike harvesting the Little Sisters (which is a choice, as the player may also save them) killing Cohen’s ex-disciples is the only way to proceed.

Once Cohen is satisfied with Jack’s work, he opens the way forward, allowing Jack to access the bathysphere and continue on, whereupon he is reconnected with Atlas who resumes providing goals.

WARNING: HERE THERE BE HEAVY SPOILERS

Bioshock’s most famous twist comes during the climactic confrontation with Andrew Ryan, toward whom Atlas has been steering Jack the whole time. Jack, it turns out, has been brainwashed, and obeys anyone who simply says “would you kindly.” Atlas, of course, has been using this control phrase throughout the game.

Ryan, it seems, accepts at this point that he is going to die. Rather than give Atlas the satisfaction, however, he hands Jack his golf club and issues the kill command himself. “A man chooses,” Ryan says. “A slave obeys.” Thus Ryan chooses his own death (suicide by player-character) while simultaneously proving that Jack is a slave, and has been all along.

It’s a shocking, horrifying moment. But here’s the problem: the player’s experience completely contradicts the narrative revelation.

From the moment Jack crosses the threshold into Ryan’s office until after Ryan is dead (the portion of the above video displayed in letterbox), the player has no control over Jack’s actions. It’s one of very, very few moments in the game where player agency is removed. So when Ryan reveals to Jack that he has been a slave all along, the experience used to demonstrate this to the player is thoroughly different from the experience both before and after. Previously, the player was not compelled to obey “would you kindly” commands immediately. They were free to delay and roam as desired. This time, and only this time, commands are acted on right away - and without the player’s agency. It’s a bit like if I said, “Look, you’ve been blind all along!” and ‘proved’ it by covering your eyes with a blindfold.

Ryan can safely shock the player with the news that they have done exactly what was ordered of them, because in order to even reach this scene the player must have done all of those things. But the mechanism by which the player was obliged to commit these acts is inconsistent with the mechanism by which Jack is compelled to kill Ryan. Jack is actively forced by his brainwashing, but the player has been, and continues to be, passively restricted by the way the game’s universe is built. The “would you kindly” requests are just layered on top of what the player had to do anyway.

To prove this, we need look no further than Sander Cohen. He compels the player to actively do horrible things - all without a single “would you kindly." Never once does he utter the magic phrase. Jack, apparently, is not forced by his brainwashing to obey Cohen. The player, however, is exactly as constrained as always. (Cohen, in fact, can be seen as a proxy for the game designers. Neither friend nor foe, he passively limits the player’s path forward until the player commits the mandated deeds.)

The story progression continues in exactly the same way after the reveal - free-roaming areas punctuated by narrative choke points. Through the exact same methods of option restriction, the player character is obliged to perform the acts laid out for him by Tenenbaum, the character who takes over for Atlas as goal-provider. She never says “would you kindly” and it wouldn’t matter if she did, as Jack isn’t brainwashed anymore. But to the player, the effect is completely identical. Tenenbaum’s goals are the only way to proceed, just as Atlas’s had been. The player has exactly the same level of choice and agency as before.

Brainwashed or not, control-phrase-triggered or not, the player’s experience is identical - except for the one moment meant to demonstrate the nature of the player character’s situation. And thus Bioshock’s commentary on player choice is, ultimately, self-defeating. It contradicts itself and the player’s own experience.

Bioshock is far from the first game to point out the player’s actual lack of freedom, nor is it the first to tie it into the plot with an in-story explanation. It’s just unfortunate that in order to maintain an interesting plot and unified gameplay, the explanation diverges from the phenomenon it is attempting to explain, greatly weakening the emotional punch of what should be the game’s most powerful moment. It is one thing to tell the player that they are a puppet. It is quite another to jerk the strings, pretend to cut them, and then continue to make the puppet dance.