Awesome By Proxy: Addicted to Fake Achievement

When I was old enough to care whether I won or lost at games, but still too young to be any good at them, I decided RPGs were better than action games. After all, I could play Contra for hours and still be terrible at it - while if I played Dragon Warrior III for the same amount of time, my characters would gain levels and be much more capable of standing up to whatever threats they encountered. To progress in an action game, the player has to improve, which is by no means guaranteed - but to progress in an RPG, the characters have to improve, which is inevitable.

As I grew older, this conclusion lay dormant and unexamined in my mind. RPGs continued to be my favorite genre. I relished the opportunity to watch interesting, lovable characters develop and interact in epic storylines. (Comparatively interesting and lovable, anyway - say what you will about Cecil, but his quest for redemption revealed a lot more depth than Mega Man’s quest to shoot up some robots.) And I loved feeling like a hero. I saved the world in Final Fantasy IV, again in Lufia II, then again in Chrono Trigger.

Then, one day in a Child Psychology course, I learned something interesting.

It turns out there are two different ways people respond to challenges. Some people see them as opportunities to perform - to demonstrate their talent or intellect. Others see them as opportunities to master - to improve their skill or knowledge.

Say you take a person with a performance orientation (“Paul”) and a person with a mastery orientation (“Matt”). Give them each an easy puzzle, and they will both do well. Paul will complete it quickly and smile proudly at how well he performed. Matt will complete it quickly and be satisfied that he has mastered the skill involved.

Now give them each a difficult puzzle. Paul will jump in gamely, but it will soon become clear he cannot overcome it as impressively as he did the last one. The opportunity to show off has disappeared, and Paul will lose interest and give up. Matt, on the other hand, when stymied, will push harder. His early failure means there’s still something to be learned here, and he will persevere until he does so and solves the puzzle.

While a performance orientation improves motivation for easy challenges, it drastically reduces it for difficult ones. And since most work worth doing is difficult, it is the mastery orientation that is correlated with academic and professional success, as well as self-esteem and long-term happiness.

In childhood, it is remarkably easy to instill one orientation or the other. It all comes down to the type of praise you receive. If you perform well on a task and are told, “Wow, you must be smart!” it teaches you to value your skill, and thus fosters a performance orientation. But if instead you are told, “Wow, you must have worked hard!” it teaches you to value your effort and thus fosters a mastery orientation.

What does this have to do with video games? Well.

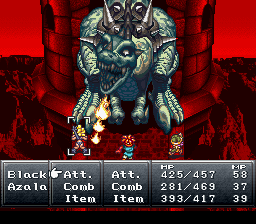

RPGs are many things, but they are almost never hard. As I realized in childhood, the vast majority of RPG challenges can be defeated simply by putting in time. RPGs reward patience, not skill. Almost never is the player required to work hard - only the characters need improve. Failing to defeat Zeromus might mean your strategy is flawed, but it also might mean your level is too low. Guess which problem is easier to remedy?

Yet while the player is mostly marking time, the characters are accomplishing epic, heroic deeds, saving lives and defeating evil. Even when the player is not explicitly praised for this, the game makes its attitude clear. “You’re awesome!” it says, in essence. “You’re so strong and noble and heroic!” The player is showered with praise for non-achievements. It’s like porn for the performance oriented.

The characters make all the effort, but the player receives all the accolades. The game doesn’t have to say “Wow, you must be smart!” to train the player to value impressiveness that was not hard-won - even when the praise is for effort rather than skill, it is a lie. The player has expended only time.

“You may have cursed this never-ending journey. You have known injury and defeat, but you have struggled on to reach this place. Your in-born intelligence and courage have helped bring you here. You have believed in your friends, and as a group, you have supported each other. Have you ever stopped to consider how much your power has grown?”

—Tenda tribe member, Earthbound

When I learned about performance and mastery orientations, I realized with growing horror just what I’d been doing for most of my life. Going through school as a “gifted” kid, most of the praise I’d received had been of the “Wow, you must be smart!” variety. I had very little ability to follow through or persevere, and my grades tended to be either A’s or F’s, as I either understood things right away (such as, say, calculus) or gave up on them completely (trigonometry). I had a serious performance orientation. And I was reinforcing it every time I played an RPG.

I could point to characters and story as much as I liked. But I couldn’t lie to myself - not anymore. Most of my enjoyment of Super Mario RPG, of Skies of Arcadia, of Kingdom Hearts - came from illegitimate sources. It came from overidentifying with the heroes and claiming their accomplishments as my own. It came from abusing them for fake achievement. I felt sick.

After panicking for a while, I came up with a plan. There was no point blaming anyone else for the state of things - I was the only one who could turn it around. So I would do so. I would instill a mastery orientation in myself.

The first thing I did was stop playing RPGs. I was addicted and I had to quit. Then, it was time to retrain myself. I started small: I began playing action games. If RPGs had reinforced my bad habits, then action games could reinforce good ones.

It’s been a long road since then - it’s not easy to reverse a way of thinking so deeply ingrained for so long. And I still have to watch myself, and not let myself be too proud or self-congratulatory when I accomplish something quickly and easily. But I feel good about how far I’ve come. And Sonic will always have a special place in my heart for the role he played in starting me down the road to recovery.

I’m not saying that everybody needs to play on the hardest difficulties they can possibly manage and devote hours to mastering every game they touch. Few of us have that kind of time or patience, and it’s better spent developing more useful skills or actually being creative or productive. I don’t play on Hard all the time, or always shoot for 100% completion. And I’m certainly not telling you not to play RPGs - I play them occasionally myself now, confident that now I’m enjoying them for the characters and story and not as a source of fake achievement. What I am saying is that you should pay attention to what’s going on in your head when you play these games.

Imagine you were watching Lord of the Rings, but there was something wrong with your DVD player and you had to manually advance scenes by hitting a button. And you might have to watch the Battle of the Pelennor Fields a few times before you could make it past the Battle of the Black Gate. Periodically Sam or Aragorn would turn to another character and say something like, “You are so brave and heroic for coming along and helping me. I couldn’t do this without you.” But these moments would always be filmed in perspective shots, with the characters speaking directly to the camera.

Would you roll your eyes, wishing they’d get on with it? Or would you feel a small but uncontrollable flush of pride? And what would it say about you if you did?

Be aware of why you play the games you do the way you do. Be aware of how you use them. We humans are remarkably adept at finding ways to lie to ourselves, and ways to be self-destructive.

There is a followup to this post.