Test Skills, Not Patience: Challenge, Punishment, and Learning

Difficulty in games is a popular and thorny subject. Are games easier than they used to be? Does easier mean worse? Are games being “dumbed down”? And how do the dreaded “casual players” fit in?

The problem with these questions is that it is not productive to discuss difficulty as a single quantity. The term “difficulty” as it is commonly used encompasses two almost completely separate phenomena, with profoundly different effects on the player:

Challenge: Tests of skill or knowledge that require mastery of the game’s mechanics to complete successfully. A strictly-timed series of jumps, a grueling boss fight, a pernicious puzzle.

Punishment: The consequences of failing a challenge. Being returned to the start of a sequence, losing money or other resources, or even being kicked out to the title screen.

Without challenge, there can be no punishment, because it is challenge that presents the opportunity to succeed and be rewarded, or to fail and be punished. Still, these are two mostly independent axes. A game can have high or low challenge levels, at the same time that it can be punishing or forgiving. Consider two games from 2008: Prince of Persia and Braid. Both games are extremely forgiving platformers - it is literally impossible to die, thanks to the Prince’s companion and Braid’s time-manipulation mechanics. Yet Braid is considered much harder than Prince of Persia - its challenge level is significantly higher.

Modern video games range widely on the challenge spectrum, and many provide adjustable challenge levels. Punishment, on the other hand, has steadily trended downward. Games have become increasingly forgiving over the years.

Most recent adventure games don’t let the player put the game in an unwinnable state, which would require reloading or restarting. First- and third-person shooters are increasingly allowing full health regeneration after a few seconds of safe rest. Platformers and side-scrollers dropped limited lives, and are now moving toward the removal of death entirely (some discussion on this evolution-in-progress here). Every genre has its own punishment conventions, and thus its own way to become more forgiving.

Why do we see such clear-cut patterns? Why do challenge levels spread out, while punishment levels overwhelmingly decrease?

It’s because both challenge and punishment have a powerful relationship to one of the most important elements of video games: learning.

Most forms of media have exactly one method of interaction. Once a person learns to read one book, they are equipped with the skills necessary to read all books, regardless of the genre, publisher, or binding. From then on, any learning that occurs is declarative, rather than procedural - the reader may encounter new and unknown words and look them up, but they are unlikely to encounter new types of pages that must be turned different ways.

Video games, by contrast, never stop teaching interaction methods. This is true on every level, from the platform (learning to use a keyboard and mouse is of only limited help in understanding how to use a Wii remote) to the genre (learning to play a kart racer will not teach someone to play a city-building sim) to the franchise (the skills required for Mario Tennis will transfer only partly to Top Spin) to the installment (Final Fantasy X plays rather differently from Final Fantasy X-2) all the way down to the specific challenges within an individual game (the stomping strategy that worked so well on the Goombas won’t be helpful against Lakitu’s Spinies). Players must constantly acquire new skills to progress.

It sure sounds like a lot of work, doesn’t it? So why do we keep doing it?

Because learning is fun. Humans are curious creatures, eager to gobble up new knowledge and abilities. Few things are more innately satisfying than being able to do something we weren’t able to do before - and then, being able to do it better. This desire to master has always been fundamental to the appeal of gaming.

“…players derive much of the fun from the gradual introduction and application of game mechanics…

…the joy of discovery and the satisfaction of finally ‘getting it’ are hard to resist."

—Rob Zacny, The Incredible Disappearing Teacher

A challenge is nothing less than an opportunity to learn. But this is only true if the challenge level is appropriate to the player’s skill level. Too low a challenge presents nothing to learn, and will likely bore the player. Too high a challenge level presents something difficult or impossible to learn, and will likely frustrate the player. Neither will engage or satisfy the player. The optimal challenge level is just above the player’s skill level - obstacles the player can just manage. My friends and I have observed this anecdotally, as it quickly became clear to us that the fastest way to improve at DDR and Guitar Hero was to play songs that we could just barely pass.

Think of the challenge level as the shape of a climb. Too easy is a flat stroll, presenting nothing of interest and failing to elevate the climber. Too hard is a sheer wall, impossible to scale and thus also failing to elevate the climber. Juuuuust right is stairs.

The player can see the path up, and knows that it can be traversed. It requires effort, but it’s attainable. And the successful climb is a satisfying process of learning and improvement. (For more on this subject, read up on Csíkszentmihályi’s concept of flow.)

Every player has their own set of experiences and their own skill levels. As gaming becomes more mainstream and reaches a wider audience, we should expect to see a greater range of challenge levels, allowing more and more players to enjoy games by having pleasurable learning experiences.

That explains challenge’s tendency to spread out. What about punishment’s decline? Again, it’s the connection to learning - and punishment, it turns out, actively inhibits learning.

Learning a skill consists of a few stages. You make an attempt, observe feedback indicating how well you succeeded or failed, adjust your strategy based on this feedback, and make another attempt. Rinse and repeat.

In Shamus Young’s absolutely wonderful video essay, Reset Button: Most Innovative Videogame of 2008, he points out the absurdity of the common video game punishment scheme by applying it to another skill-based activity: basketball. Learning to shoot hoops would be a lot less fun if every time you missed the basket, you were sent home and had to walk back to the court. It would be annoying and time-consuming. But it’s actually even worse than Young indicates. Not only does punishment break up and drag out the learning, it erodes it.

If you throw the ball at the basket and the shot bounces off the right side of the backboard, you aim a bit further left on your next attempt. But if you have to walk back to the court after the first airball, by the time you get there your muscles won’t remember exactly where you were positioned before, and you won’t know how to compensate. The value of the feedback decreases tremendously when you have to wait to act on it.

Now imagine that on your way back to the court, you have to use a completely different skill set - climbing over obstacles and dodging careless skateboarders. How can you possibly remember how you set up your last attempt? The feedback has been almost completely obliterated. In seconds, you miss the basket again, and are consigned to your learning-disruptive walk once more.

Suppose that this had been the only way to learn basketball for decades, and then someone created a basketball court that did not eject players when they missed a shot. Would the “hardcore” basketball players bemoan the “dumbing down” of basketball? Would they spit vitriol at the “casual players” this move is ostensibly designed to attract?

After all, without punishing failure, how does one sufficiently incentivize success? Punishment as a consequence for failure creates a fear of that failure, lending urgency and emotional weight to the challenge. But is that really true? Does punishment motivate, or frustrate? Does punishment create fear or annoyance?

“Creating real fear requires immersion, and sending the player back to the loading screen kills that. A second ago they were afraid for their lives. Now they remember they’re in their living room, it’s all just a game, and the danger was never real to begin with. You can threaten them all you like but once you actually kill the character, the player will remember you’re all bark and no bite because you can’t really hurt them. The worst you can do is stop them from progressing in the game, which just isn’t all that terrifying."

—Shamus Young (again), You Don’t Scare Me

Punishment isn’t scary, but it’s certainly unpleasant. It’s annoying and often repetitive, and it’s also insulting. It’s a face-slap, a knuckle-rap, a disapproving cluck. It’s penance the game imposes on the player for performing disappointingly. It motivates the player, all right - not to succeed, but to avoid punishment - which means avoiding risk of failure.

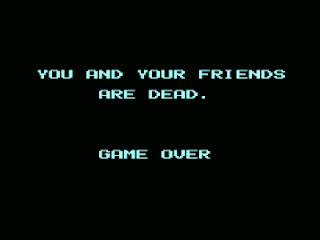

A player who dreads seeing the GAME OVER screen and being sent back to the title is much more likely to give up and visit GameFAQs than stick with a challenge until they have mastered it on their own. This player will learn less, and in a much less satisfying way. Punishment is downright damaging to the learning process. The opportunity to fail freely is vital.

“People remember things better, longer, if they are given very challenging tests on the material, tests at which they are bound to fail. In a series of experiments, [researchers] showed that if students make an unsuccessful attempt to retrieve information before receiving an answer, they remember the information better than in a control condition in which they simply study the information. Trying and failing to retrieve the answer is actually helpful to learning."

—Henry L. Roediger and Bridgid Finn, Getting It Wrong: Surprising Tips on How to Learn

(referencing research performed by Nate Kornell, Matthew Hays and Robert Bjork at U.C.L.A.)

Failure itself is sufficient to motivate learning. The simple absence of success makes us want to succeed. Punishment is dead weight, and removing it streamlines the learning process, while increasing fun and satisfaction.

Until the entire video game community understands the difference between challenge and punishment, developers will continue making the same mistakes, and players will continue to berate the developers who avoid these mistakes. Consider the case of Bionic Commando Rearmed.

Rearmed is an enhanced remake of the NES game Bionic Commando, released twenty years earlier in 1988. Lovingly faithful to the source material, but giving it a fresh paint job, new features, and upgraded boss fights, Rearmed was extremely well received, selling over 130,000 units during its first week. But game design has come a long way in twenty years, and some of the mechanics carried forward seem outdated now. In particular, Rearmed maintained its predecessor’s use of limited lives, ejecting players from levels when they died too many times.

Nearly a year after the game’s release, it was patched. The patch did a few things, but one of them was to remove the limited lives system. And what was the community response?

“Yesterday it appears that a patch was released for Bionic Commando: Rearmed over PSN. The update is a bit of a mixed bag, unless you’re a total wuss and can’t beat the game as it is. See it does allow for Trophy support, which is good. However, along with the Trophy support comes some changes to the games basic gameplay. Players now have unlimited lives (no starting levels over from the beginning), can swing into walls without falling to their untimely deaths and can reel out their line if it is too short. These features make the game immensely easier, betraying its old school roots.

Thankfully the update only tweaks the easy and normal levels, but that doesn’t really excuse it. Who was out there complaining that BC: Rearmed was too hard, especially on easy and normal? Nancy-pants girlie men that’s who. For now 360 owners can walk around claiming they have bigger nerd balls as the update does not appear to have landed on LIVE yet. PS3 owners, your cred is in question until the 360 wusses out too or Demon’s Souls lands."

—Matthew Razak, Bionic Commando patch is up, makes PS3 owners girlie men

This commentary is clearly not meant to be taken completely seriously, but the attitude behind it and the message it sends is clear - and thoroughly misguided. Rearmed’s patch is, more than anything else, a reduction in punishment, not challenge. And the fact that Razak is thankful for - the changes only applying on Easy and Normal, and not Hard or Super Hard - is an awful, awful mistake.

By leaving punishment intact on the higher difficulty levels, the Rearmed patch reveals an assumption that follows naturally from the fallacious conflation of challenge and punishment - the player must want both or neither. There is no way to experience the game’s full content and master all of its challenges, without also suffering through its heaviest punishments. The problem is that high challenge magnifies the downfalls of punishment by guaranteeing that the player will be subjected to it over and over again. The more there is to learn, the more destructive is the disruption of the learning process. Increasing both challenge and punishment at the same time is a surefire way to prevent learning by frustrating players and driving them away.

Rearmed is hardly a unique case. Throughout the gaming community, challenge and punishment are treated as equivalent components of “difficulty,” and the results shortchange developers and players alike. Constructive debate is nearly impossible, as all attempts to mitigate punishment are seen as equivalent to attempts to remove challenge. Progress, therefore, is slower than it might be. But it does occur. And the market has a tendency to reward it.

Consider Braid, briefly mentioned above. A puzzle-based side-scroller developed by Jonathan Blow, Braid has some of the most forgiving game mechanics yet seen. Due to player-character Tim’s limitless ability to rewind time, all mistakes can be undone. That includes death. There is no running out of lives; there is no Game Over. Yet the game presents some fiendishly challenging puzzles, requiring non-linear thinking and an understanding of the consequences of some decently-elaborate temporal manipulation.

In Braid, Blow quietly offered up high challenge coupled with an extremely forgiving environment in which to master it. And people loved it. Several reviewers called the game a “masterpiece.” It holds a Metacritic score of 93. It sold about 55,000 copies in its first week and was “very profitable” for Blow.

And thusly the state of the art advances. The great debate rages on, going nowhere, but periodically a game comes along that lowers the punishment another level, and sells well enough to be imitated. Soon enough, the previous level of punishment feels old and outdated. So while it might not be easy to say out loud, every once in a while it’s proven through action: punishment is not challenge, and its role in the modern video game is - and ought to be - rapidly disappearing.

There is a followup to this post.