I'm Not Evil, I Just Play That Way: Player Motivations and Character Goals

Recently we took a look at the technique of option restriction, which is when a game presents the player with only one path forward, thus eliminating choice while maintaining agency. If it’s handled well, it allows for close management of narrative progression while still letting the player feel that they are in control. So what is it that determines whether it’s handled well? What allows the player’s sense of control to be maintained even with a lack of choice?

“Players like to feel in control, but this sensation doesn’t necessarily come from having the ability to choose. Having control is as simple as doing what you want to do. It’s possible for players to feel in control even if they don’t actually have the ability to choose, as long as the what the game asks and what the player wants aligns. A good narrative should foster this.”

—Andrew Vanden Bossche, Would You Kindly? BioShock And Free Will

As long as what the player has to do is what they would want to do anyway, there’s no conflict. A well-crafted narrative will direct the player’s motivations to the options that are actually available. It’s when the narrative fails that the player wants to do something they can’t, or specifically doesn’t want to do what the game allows. This is where option restriction ceases to be fun, and becomes confining and frustrating.

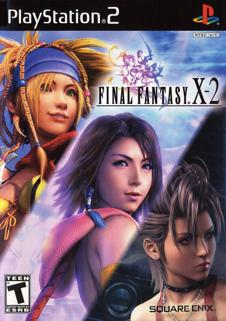

YUNA: This is where we sat that night, the seven of us. I’ve never talked about it. I didn’t want to share my memories. I wanted to keep that feeling, this place within me forever. Now look at it.

(All Final Fantasy X-2 quotes are from Final Fantasy X-2: Game Script by Asch The Hated.)

Yuna soon runs into an old friend - Isaaru, an ex-Summoner like Yuna who has had to find new purpose in a world without Sin. He now works as a Zanarkand tour guide. When it becomes clear that Yuna and her friends do not approve, the following exchange takes place:

ISAARU: I can see this is upsetting you. But this is a place of great historical importance for all of Spira.

YUNA: I know. But, still… I never wanted anyone else to stand there.

A bit later, he explains his job this way:

ISAARU: I bring excitement to those who’ve come to see this sacred place. I, too, once traveled with the hope of seeing this place someday. Working here somehow fulfills that wish.

When Yuna returns later in the game, Isaaru reports that business is poor. The local monkey population has been increasing, and the monkeys are harassing the tourists. This prompts a discussion between Yuna’s companions.

RIKKU: Hey, if there were more of these little guys, you think the place would empty out?

PAINE: It just might.

The player is then presented with a quest to play monkey matchmaker - finding mates for the unattached monkeys so that the monkey population will grow even faster, to the point where tourists will not dare to visit.

The problem is that the game’s narrative has completely failed to present Yuna’s motivations in a sympathetic light, and so the player is unlikely to share them. Yuna does not come across as the protector of a sacred space. Instead she appears childish, selfish, and destructive. She wishes to prevent the people of Spira from having the chance to visit a place of great historical and spiritual import because she wants to keep it for herself - and somehow, having it swarmed with monkeys is preferable than having it appreciated by tourists. And she’s perfectly willing to put her friend Isaaru out of a job along the way.

If the player isn’t feeling quite so petty, then they are unlikely to want to participate. The disconnect between what the player and player character feel greatly disrupts immersion and identification, and the disconnect between what the player wants to do and what the player is allowed to do destroys the feeling of control and replaces it with frustration.

The attempt to avoid these disconnects may be why games in general tend to have such stark morality. When there is a clear-cut right and wrong, and the player character is on the right side, the character’s goals are likely to appeal to a very wide audience of players - or at least not repulse them.

But while these serve well as common minions, they aren’t quite so satisfying as central or final bosses. These, by contrast, tend to be much more human, intelligent, and self-directed. Consequently, their irredeemable evil must be demonstrated narratively.

Thus, while most minions will never been seen or heard from until they confront the player, ready to be dispatched, final bosses tend to show up well before the player can do anything nasty to them, and prove they deserve it ahead of time.

“Using highly sophisticated technology - which you couldn’t possibly understand - we will be extracting a large portion of your planet and adding it to our new one. Unfortunately, this change of mass will cause your planet to spin out of control and drift into the sun where it will explode in a flaming ball of gas. But of course, sacrifices must be made.”

—Chairman Drek, Ratchet & Clank

Unsympathetic villains have literally been a rule for certain other media when they were a bit younger. The Hays Code stipulated, among other things, that “…the sympathy of the [film’s] audience should never be thrown to the side of crime, wrongdoing, evil or sin.” The Comics Code Authority held that “Crimes shall never be presented in such a way as to create sympathy for the criminal…”

These rules were created to prevent the audiences of films and comics from being corrupted, and because film and comics were not respected as art. (In fact, the Supreme Court ruled in 1915 that movies are not art and therefore not protected by the first amendment - they did not overturn the decision until 1952.) However concerned people were in these times that movies and comics would be a corrupting influence must surely go double for video games, in which the audience has actual agency.

It should not be so surprising, then, that the moral spectrum is so limited in most video games. But this represents, more than anything else, a failure to recognize and make use of the narrative power of the medium, instead simply using it to tell modern morality plays. Nor should it be so surprising that while the industry as a whole is recognizing that players may want a bit more flexibility, they are generally not doing it in a very subtle way.

“I’m sick of games that claim to have ‘choice’ but that only really come down to either Mother Teresa or baby-eating. All I’m saying is that a little middle ground is nice now and then.”

—Ben “Yahtzee” Croshaw, Zero Punctuation: BioShock

If games commonly present a simplistic moral framework, and players become tired of playing simplistic heroes, it’s easy to picture game developers scratching their heads in confusion. How could anyone not want to do these obviously noble deeds? They must want to be completely evil. And so then we get games that let you choose between simplistic hero and simplistic villain, when it was the “simplistic” bit that was the problem all along.

Real-world morality, of course, is extremely complex. It is far more interesting to explore moral questions that share some of this complexity.

“The Choice between Good and Bad is not a matter of saying ‘Good!’ It is about deciding which is which.”

—The Lord of Dark, The Sword of Good by Eliezer Yudkowsky

The degree to which developers understand and apply this varies. BioWare’s Mass Effect presents a Commander Shepard who is a hero, but what kind of hero is a choice left up to the player.

“Commander Shepard is a hero. The choice between the Paragon and Renegade path is one of compassion versus ruthlessness. A compassionate Shepard will try to minimize the negative impact on innocents. A ruthless Shepard minimizes risk on his mission, even if there’s some collateral damage. Both Paragon and Renegade Shepard share the same desire to succeed in their mission, though, and Shepard’s mission is always heroic. There’s no option to walk away and let everyone die, because Shepard just wouldn’t do that.”

—BioWare Lead System Designer Christina Norman, as quoted in Revisited: Mass Effect’s ‘Bring Down the Sky’ DLC

Their more recent Dragon Age: Origins takes things even further:

“We’re trying to be a lot more grey than that, aggressively. . . . You have characters that have their own motivations, opportunities for you to be opportunistic, and maybe do something that’s inherently evil but at the same time, a part of being a Grey Warden and carrying the fate of the world on your shoulders, maybe it’s what you think you have to do. It’s a choice you have to make.

We’re also trying to give you, I guess, a sense that the villains, the characters you’re interacting with, they have real motivations for why they’ve done what they’ve done. So while it’s very easy at first to go ‘well clearly he’s the bad guy,’ as soon as you dig in deeper and the game certainly encourages you to do this, you tend to find there’s more going on than just the surface.”

—Lead Designer Mike Laidlaw, as quoted in Dragon Age’s Moral Choices Will Be ‘Aggressively Grey’

Sympathetic villains and questionable acts that nonetheless must be done for the greater good create tension between player motivation and character goals, rather than conflict. When the player is made to do something unappealing or fight someone who doesn’t deserve it for reasons that the player can accept, it is not narrative failure but emotional depth. The player may experience frustration, but if so it is as a result of identification with their character’s plight, and not directed at the design of the game.

Ethical tension is the lifeblood of the Metal Gear Solid series. The player characters are sent into life-and-death conflicts by commanders who know far more than they are telling. As the player learns more and more about what’s really going on, the questionable morality of their character’s actions becomes increasingly prominent - but so does their obvious necessity. Due to the emotionally intense nature of these experiences, any worthwhile example will necessarily constitute a spoiler. I’m not going to spoil any of them here, but for a pretty good example, take a look at the events of Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater (with particular attention to the “Life’s End” and “Debriefing” sections).

Video games are a young medium. They face the same trials and prejudices faced by other media in their youth. As a result, there is an all-too-typical fear of stories with complex or ambiguous ethics. This combines with a desire not to force too many players to do things they wouldn’t want to, with the result that many games only offer up a stark, uninteresting moral canvas.

This is not necessarily a bad thing. We don’t really need to know why the Space Invaders must be destroyed in order to have fun shooting them down. But mature media are unafraid to explore deeper, crafting narratives that usher players into places where they might not be so comfortable. When they’re poorly done, these stories just frustrate us. But when the narrative matches up player and character motivation, then these are the stories that haunt us. These are the stories that change the way we think. These are the stories that make us grow.