Tropes and Trolls: When the Game Is Not What You Think It Is

In games where the player character has a specific goal - save the Princess, escape the testing facility, defeat a nemesis - the player is presumed to share this goal. But even if the narrative does a good job lining up player motivations and character goals, there’s still a wrinkle. The character wants to accomplish something, and the player wants to experience accomplishing that thing. This is why we bother playing games at all, rather than just watching the endings on YouTube. If the player had the exact same motivations as the character, they’d cut whatever corners they could to beat the game as quickly as possible.

The humor in this video comes from the tension between Mario’s goals and the player’s goals. Of course Mario would want to just warp straight to the Princess and save her immediately. But for the player that would mean skipping the entire game, which would completely defeat the purpose of playing it in the first place. As long as Mario has that warp whistle in his inventory, there’s dissonance between what the player wants to do and what Mario would want to do.

So what happens when games create that dissonance on purpose?

Get Home is a brief flash game. If you want to experience it unspoiled, check it out now. It’ll only take you a few minutes.

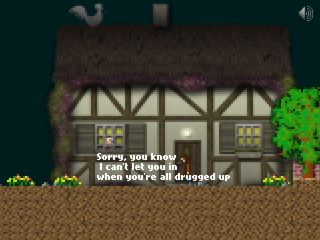

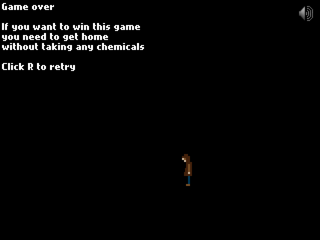

The goal of Get Home is right in the title: get home. Heading to the right reveals a series of platforms leading to powerups that allow the player character to jump higher and move faster, granting access to further platforming challenges, until finally the character can actually fly. The character arrives home - and is denied entry, because the powerups were actually drugs that cause unpredictable behavior.

Playing a second time, the player may notice an alternate path. Instead of climbing the initial set of platforms, the character can head right past them and continue on a straight shot to a very brief and simple platforming section that leads directly home. Having taken none of the powerups, the character is welcomed in.

The game is a deconstruction of common platformer tropes. Most players will instinctively jump up the first set of platforms without questioning the powerups found along the way. This behavior may be unrealistic, but it is completely natural to anyone who’s played platformers before. The game, therefore, exists to remind us that we’re making assumptions that are not necessarily correct - they’re just what we’ve been trained to believe.

But there’s a problem: the game cheats.

Apart from this one mistake undermining what the game sets out to do, Get Home is a well-made and largely successful examination of the way game tropes are internalized. It’s just the right length and it’s actually fun. Or at least, it can be.

Taking the powerups and tackling the platforming challenges is fun. Walking straight to the right is not. But the latter playthrough is the only one in which the player character achieves the goal of getting home. It is not possible for the player to have fun while accomplishing the character’s goal. They can only do one or the other on a given playthrough.

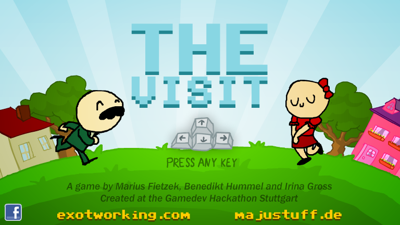

The Visit is another brief flash game that takes a different approach to internalized tropes and the assumption of fun. Again, if you want to experience it unspoiled, check it out now. This one also will only take a few minutes.

In The Visit, the goal is to visit the player character’s girlfriend. As with Get Home, it presents as a standard 2D platformer, though a bit more directly inspired by Super Mario Brothers. Heading to the right, the character encounters some easily-jumpable obstacles and a crab that is clearly a stand-in for a Goomba. Most players will act on pure trope-fueled instinct and jump onto the crab, killing it. At which point the player character is suddenly arrested and tried for murder.

Like Get Home, The Visit pokes fun at the assumptions players make in games that look and behave a certain way. It’s a little less honest about it, however. It turns out that the crabs are people too, but this is not at all obvious from the way they behave before one is killed. At first, the crabs just walk back and forth with a mindless smile on their face, not reacting at all to the presence of the player character. It’s only after one is killed that they begin acting like intelligent members of society.

On top of this, it’s surprisingly difficult to avoid killing the crabs. While walking through them is harmless, jumping or falling onto them causes a fatal squishing. And they often walk in places where it’s not at all trivial to avoid landing on them.

While it’s not the outright option restriction employed by Get Home, The Visit uses several tricks to push the player into a bad ending. Earning the best ending (by making it to the girlfriend’s house without killing any crabs) is less a matter of examining assumptions and more a matter of understanding the game’s deceptions. It’s not really fair for the game to chastise the player for falling for a lie.

Unlike Get Home, however, the fun way to play is also the one that accomplishes the character’s goals. After the first crab kill, when the results are no longer novel, killing a crab is simply an instant failure mode with an all-too-long delay before the next attempt. Avoiding the crabs presents the game’s only real challenge and fun. Thus the player absolutely has the opportunity to have fun accomplishing the character’s goal - once they understand what it is.

Spec Ops: The Line also plays with established tropes and the player’s desire to have fun. It’s not free and it’s longer than a few minutes, so I’m not going to spoil it nearly so heavily. Still, if you plan to play it completely fresh, now would be the time to stop reading. (Alternately, if you want a closer but spoiler-laden look, check out Skill Up’s excellent video on the subject.)

A couple of hours in, however, things start changing. It becomes increasingly clear that this game is not a traditional power fantasy. Walker isn’t a super-soldier who can waltz into danger and save the day by shooting enough people. He’s an impulsive fool with a hero complex who’s in way over his head. Everything he does makes the situation worse and causes substantial psychological damage to him and his squad.

Like The Visit, Spec Ops: The Line asks the player to consider the consequences of their actions rather than charge forward and kill others simply because they are in the way. Yet while The Visit asks the player to take seriously something that is obviously silly, Spec Ops’s subject matter is deadly serious. The people Walker kills are not cartoon crabs. They are realistic human beings modeled after the citizens of a real city and the members of actual government and military organizations.

Spec Ops doesn’t just point out the assumptions that players make based on genre tropes. It outright attacks those tropes as irresponsible. It suggests that we shouldn’t be making or playing games that employ them. The games whose tropes are being sent up in Get Home and The Visit provide fun through joyful motion and cartoon violence. The games that Spec Ops attacks drape themselves in military pageantry and present pastiches of complex real-world geopolitics that can be solved by walking forward and shooting enough people. Worse, they present these situations as fun.

François Truffaut famously stated that there is no such thing as an anti-war movie, because the action always looks exciting on the screen. In any game designed to be fun, it’s similarly impossible to convincingly claim that war is hell.

“The burning question would be then, is there a way for the developers to avoid falling victim to Truffaut’s dilemma? Within the framework of game design, I would say that there isn’t. Games are designed as a form of recreation, and with it being big business nowadays, that agenda is going to continue."

—Pylades, Your Turn: Truffaut was right

Spec Ops: The Line sidesteps the problem by being purposefully unfun. The player is intended to start out having a good time, but by the end they should be shaken or outright nauseated. Walker can never reach his destination and the player is not intended to enjoy the journey.

It’s not a new idea that art can do more than entertain. Schindler’s List isn’t much fun, and neither is The Great Gatsby. Catharsis is a literally ancient idea. But for games, the common wisdom is still that they can only be about fun, and have no access to a broader emotional palette.

Unseating this assumption is an uphill battle. Games that deal with important, sensitive topics are rarely seen as evidence of the medium’s expressive power. Instead they are accused of trivializing their subjects, and more serious subjects cause more anger. (See, for example, the reactions to Super Columbine Massacre RPG! and Six Days in Fallujah.) So while Spec Ops: The Line’s message that we should not be so eager to play soldier is more socially relevant, games like Get Home and The Visit are just as subversive, and for right now may even be more important. These games provide approachable, bite-sized, low-stakes experiences demonstrating that there is more to games than simple fun. In so doing, they show that games like Spec Ops: The Line are even possible.