Play Me A Story, Part Two: What Makes A Metanarrative?

Whether you’re watching a DVD or playing a video game, you have control over the progression of the experience. You may hold a remote or you may hold a controller, but the action on the screen will start, stop, pause, and continue, in response to the buttons you press.

The fundamental difference is the degree of choice you hold. With a movie, you can only choose whether to proceed. With a game, you choose how to proceed. Even subtle or trivial decisions, such as on what path to move your character, or which weapon to use on enemies, or where to position the camera, engage you in the creation of your own experience.

“My older boys have been playing Super Mario Galaxy for the Wii since they were four and six, and there is more decision making in ten seconds of that game than there is in ten hours of Candy Land or Sorry.”

—Danny Choo, The case against Candy Land

Yet few would argue that Super Mario Galaxy tells a story about the player, rather than one about Mario. It presents the player with choices, but this is not enough to make it a metanarrative - a story about its own audience - any more than crossing out a character’s name in a book and writing in the reader’s name instead will cause the book to be a metanarrative about the reader.

So what does make a metanarrative? What must the decisions be like in order to confer narrative power, responsibility, and focus to the player? What do they have to do?

A small handful of specific things, it turns out - which is not the same as easy things. Metanarrative is hard, more so because we’re still figuring out what we can do with it. But that’s exactly why it’s so exciting.

1. Choices must be free.

Sometimes it is obvious that a choice is no choice at all, as in the Dragon Quest example pictured below. It is impossible to advance the story or even exit the dialog until you tell the princess that yes, you do in fact love her.

'Cuz I can't maaaaaake you love me... if you dooon't...

A closely-related tactic is to simply ignore the player’s choice - perhaps with a line of chiding dialog from another character if the player has chosen “incorrectly” - and press on the same way regardless. This method crops up in too many RPGs to count, often when presenting the player with the choice to accept or reject accept a plot-relevant quest or new party member.

More insidiously, choices can be made to look free while actually leading the player to a particular outcome, by way of a connection to game mechanics. Choosing one option leaves the player noticeably better off in terms of the game’s goals than choosing another. Many choices in Indigo Prophecy take this form. For example, when Lucas Kane seeks help from his brother Markus, a Catholic priest, Markus offers Lucas a crucifix, over the latter’s protestations that he doesn’t really believe in “that stuff”. The player then decides whether Lucas takes the crucifix - and if taken, it confers the rough equivalent of an extra life.

Clearly this choice isn’t forced, exactly, but it is made under some duress. It becomes not about faith, not about brotherhood, not about Lucas either shutting down Markus’s awkward gesture or letting him feel like he has helped in one of the only ways he knows how. It’s about getting a 1-Up. The choice has been replaced with a puzzle with a correct answer, no freer than a question on a multiple-choice test. (A more thorough examination of this idea can be found here.)

For a choice to be free, the player must not be forced or bribed into the “correct” option.

2. Choices must be affirmed.

In the first few Warcraft games, players can play either side of the Orc versus Human war. The campaigns are simultaneous, however, and thus contradictory. (It’s similar to many fighting games - the player can lead any competitor to victory, but clearly they cannot all win the tournament.) The tide of the early battles changes the circumstances of the later ones, until the final conflict ends with the player’s chosen side decisively winning the war. But then when the sequel comes along, there is a problem: how can a game continue a story whose previous chapter has been told two opposite ways?

The solution used in Warcraft is to simply pick one of the two branches and continue it, ignoring the other. Thus a canonical history is developed. The Orc campaign ofWarcraft: Orcs & Humans was revealed to be the correct one by Warcraft II: Tides of Darkness, which in turn was revealed to have been won by the Humans in the subsequent expansion, Warcraft II: Beyond the Dark Portal.

The problem with this solution is that it completely invalidates the player’s choice. Regardless of the player’s actions, one of the campaigns is what really occurs, and the other is a non-canon fantasy. Interactive fan fiction.

Sorry! This never happened.

(This may be why Blizzard’s strategy changed, and subsequent Warcraft and indeed Starcraft games have instead featured sequential campaigns in a single storyline, leaving no ambiguity to be resolved by the next installment. Rather than continuing to doom plot-branching choices to negation, they have simply removed them.)

By contrast, the Mass Effect franchise takes great pains to respect the player’s choices. The first game’s hero is Commander Shephard - but most of the details beyond this name and rank are up to the player. Gender, appearance, and first name are all customizable, and the player may select between a variety of backgrounds and skill sets. Throughout the game, Shephard is confronted with decision after decision - some minor, some life-and-death, some galaxy-shaking. Individuals can be killed or rescued; colonies can be saved or destroyed. Each player’s Shephard and the universe he or she lives in are unique.

And the sequel will respect every iota of customization and choice from the first game. Players will be able to import their save files and carry forward with their Commander Shephard, in their universe.

Even the tie-in novels respect the player’s choices - the first is set twenty years before the first game, but the second is set after the first game, and is quite careful not to refer to any details that would invalidate any possible Shephard.

The overall message, strongly broadcast, is that there is no one true Shephard - and therefore all Shephards are true. Every Shephard is just as real and genuine as every other. The franchise affirms the player’s choices by placing them on equal footing with canon, rather than subservient to it.

For a choice to be affirmed, every option must be treated as a legitimate part of the game’s universe.

3. Choices must be expressive.

Decisions pervade the modern gaming experience. The exact actions performed in their exact order and with their exact timing (walk this direction for two seconds, turn a bit to the left, and jump - or select a fire spell, select a target, and cast - or go north, look, and take ye flask) are up to the player, but the vast majority of these decisions are perfunctory and not very interesting.

Even a more concrete, deliberate decision such as which fork of a dungeon shall be explored first is not very compelling. It’s an arbitrary, meaningless decision. There is nothing of the player’s voice in it.

However, consider the moment in Bioshock when the player first finds a Little Sister separated from her Big Daddy guardian. Two other characters play the part of shoulder angel and devil - one begs you to have mercy on this poor little girl, promising to find a way to reward you for doing so, while the other implores you to kill the creepy child for the precious Adam she carries, promising that it is very important to your continued survival.

At least they call it "harvest" and not "slaughter."

This is a much more interesting decision! The player must choose between selflessness and pragmatism. Which is more important - the life of an innocent, or the safety of one whose actions may save many more lives? Such a decision unavoidably reveals something about the player (or at least the persona the player is adopting, which in itself still says something about the player). The more the player reveals, the more the player character becomes patterned on the player, and the more the game is about the player.

Expressive choices allow the player to define the player character the way they want to, and to tell the story the way they want to.

For a choice to be expressive, it must allow the player to say something about their personality or priorities.

4. Choices must be consequential.

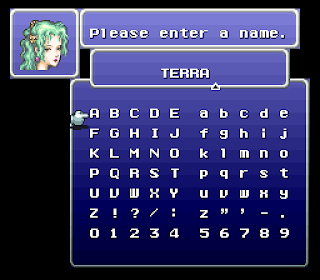

Final Fantasy VI features fourteen recruitable party members. Each and every one is presented to the player to be named. A default name is provided, but the player may choose any name of up to six letters. The game’s text and dialog will always refer to the characters by the names the player has chosen, but it’s essentially just a search-and-replace operation. The story, the people, the events, the world, remain unchanged.

A Terra, by any other name, would be just as emo.

Star Ocean 2 keeps careful track of how much your up-to-eight party members like each other, in both a friendly and romantic context. Many of the game’s optional “Private Action” events feature interactions between these characters, and allow the player to make choices that directly affect their “relationship values.”

These scenes are often amusing and fun in their own right, showing sides of the characters you don’t normally see during battles or exploration. But they also carry in-game consequences.

Certain scenes will only occur if the characters involved like (or sometimes dislike) each other enough. If two characters become close friends, and one sees the other fall in battle, the one is likely to call out the other’s name and enter a berserk rage. And once the final boss has been felled, the endings the player sees are determined by which allies like each other how much - any two can pair off and set out together, and each pairing that occurs prompts the display of a scene of what they get up to after the game ends.

These consequences lend weight to the player’s actions. The player has a genuine effect on the people of the game’s world. What the player does matters.

For a choice to be consequential, it must have a nontrivial effect on the game’s plot, characters, or world.

Thus we have our four criteria, our four rules for metanarrative choices. When a choice is both free and affirmed, it is a valid choice. Valid choices make a game’s story interactive. When a choice is both expressive and consequential, it is a meaningful choice. Meaningful choices make a game’s story dynamic. Only an interactive story can be dynamic, and only a dynamic story can be about the player.

Not every game needs to have a metanarrative. There is value across the narrative spectrum, just as there is room for the summer blockbuster movie and the independent art film, the trashy romance novel and the experimental literary epic. And developing a customizable, player-tailored experience can be quite an expensive process, often involving the creation of content that some or most players will never see.

But consider Tom Francis’s experience with Oblivion. In Francis’s game, a peculiar bug caused an NPC named Thedret to develop the quirk of always standing with his arms outstretched in an amusing pose. This simple fact caused Francis to develop a strong emotional connection to this NPC.

“I love my Thedret because no-one else has one. It took Valve six years to make Alyx a likeable aide, but this piece of sloppy code has made Oblivion’s Thedret far more important to me. I won’t fall in love with Alyx until there’s something special about my Alyx. Even if it’s just that she likes to stretch.”

—Tom Francis, Why I Love Thedret The Exaggerator

The allure of a unique, personal experience is powerful, and the ability to deliver one is what sets video games apart from all other narrative media.

Put another way, we like stories we can see ourselves in. We enjoy the chance to be the star. It’s a lot easier to love a game when the game so clearly loves us right back.