Tweet

I want to play Smash Bros on my PS3 over Xbox Live.

Welcome to Pixel Poppers; my website for talking about games. The newest posts are below; you can also check out the about page if you’re new here, search the site, or grab the feed.

I want to play Smash Bros on my PS3 over Xbox Live.

#NowPlaying Knights of the Old Republic (PC). Expecting force powers, dialog trees, and the Campbellian monomyth.

Read more...

Once upon a time, people didn’t buy video games. They went to an arcade, and bought playtime in twenty-five cent increments. How much time a quarter bought was completely dependent on the skill of the player. An unskilled player would find their progress barred quickly, and need to supply more quarters. A skilled player could proceed much longer, and was thus rewarded for the time, effort, and money poured into gaining their skill. The public nature of the arcade also rewarded the skilled player with the opportunity to show off in front of others. This provided the unskilled players with something to aspire to and suggested that it would be worthwhile to keep feeding the machines with quarters, so that they too might someday bask in similar glory. So it made a great deal of financial sense for arcade games to feature limited lives with more available for purchase.

Eventually video games moved from the arcade to the living room. Here it was much harder for a player to compare themselves to other local players, and there was no need to keep the quarters flowing since games were purchased outright. The reasons to limit lives had vanished, and barring the progress of unskilled players now served mainly to disrupt the experience and prevent those players from seeing all the content of the game for which they had already paid. This limited the games’ potential audience - why buy a game you can’t expect to make it through? Financially, it made no sense whatsoever for games played in the home to feature limited lives.

But that didn’t stop them from doing it anyway. From the original Super Mario Brothers on the NES all the way up to New Super Mario Brothers on the Wii, mainstream games have still not completely shaken off the limited lives trend. Why?

Read more...The game is called “Prince of Persia.” But it’s not really about the Prince. (He doesn’t even seem to be a prince this time. We call him “the Prince” because he has no name.) Really, the game is about (legitimate princess) Elika.

As the game opens, the Prince is lost in a sandstorm, calling out for Farah. Franchise veterans will recognize the name as that of the love interest from the Sands of Time trilogy - but it is soon revealed that Farah is actually the name of this Prince’s donkey, laden with the riches the Prince has recently looted.

It’s a nod to the previous games, but it’s also a dig at Princess Farah’s characterization and gameplay role. She was little more than a pack animal. The Prince, lost in the storm, is trying to reconnect with her, trying to return to that simplicity. Instead, he finds Elika.

Read more...I have a cold today.

I could feel it coming on yesterday, and it sent me early to bed, but today it is full-blown. I’m not gonna lie - I’ve always kind of liked being just a little bit sick. Sick enough to guiltlessly stay in bed playing video games all day (punctuated by naps and plenty of fluids) but not so sick that I can’t enjoy it.

I could play Prototype - the game I’m lately live-tweeting. But when I’m sick, I want a game that takes me to a happy place. Prototype may be a hell of a lot of fun, but it is sure not happy. Alex Mercer’s New York is a hellhole and his life is horrible. I may have a great time behind the controller, but he’s having a terrible one on the screen.

The whole point of escapism is that you escape to a better situation, not a worse one. Prototype is great for blowing off steam, but if I want to bury myself in another existence for a while, to forget about this one and the runny noses that come along with it, I play a game like Star Ocean.

Read more...I don’t usually post anything in the middle of the week. This isn’t a normal, full essay. But I had to get it out there. I had to save people who might otherwise have bought this game.

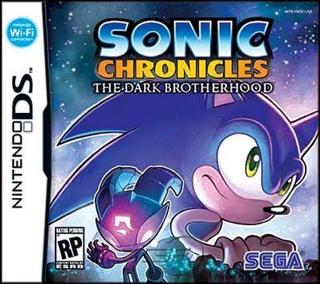

Sonic Chronicles: The Dark Brotherhood is a terrible, terrible game. Did you notice I didn’t link the title to the Amazon page? That’s because I don’t want you to buy it. I don’t even want to risk the possibility of you accidentally buying it. I can only imagine the wrath I would have right now if I had paid any money for it myself. As it is, I ripped it right out of my DS, stuffed it back into the GameFly envelope, and shoved it into the mail slot with as much contempt as I could muster.

Read more...#NowPlaying Prototype (PS3). Expecting to be an unrepentant superpowered jerfkace. Well, maybe a little repentant.

Read more...A while back, I discussed my experiences with the dangers of fake achievement and its potential for abuse. I’d become addicted, and regularly played RPGs to feel good about myself - I allowed myself to glow in the praise directed at my characters for their world-saving heroics, when all I’d really done is hit the right buttons enough times. Once I figured this out, and realized it was preventing me from accomplishing anything real, I set about the lengthy task of recovery. Step one was a game accomplishment that required skill rather than patience - collecting all the emblems in Sonic Adventure DX.

The response to this essay was… mixed, to say the least.

There was one comment in particular that raised an interesting question, which I would like to address today.

Read more...Now playing: WET (PS3). Expecting a Bad Good Game. I kinda love Bad Good Games.

Read more...

I’ve met a lot of Firefly fans. I’m one myself. Apart from enjoying the show, we all have one thing in common: we want there to be more Firefly fans. We want to share the show with others. We want more people to have the experience, to know how great it is, to laugh at the jokes and fall in love with the characters. We want more people to talk with about the show, who will know what we’re talking about and share our enthusiasm. We want more people to buy the DVDs, to cast an economic vote of “more like this!” so that maybe Joss’s next show won’t get screwed over.

It’s an inclusive fandom. We want there to be more of us. More Browncoats is better.

Read more...