ONE WRONG THING: The Hand of Fate

Why it’s wrong to kill the player character in The Hand of Fate.

Read more...Long-form articles on the art, design, culture, and psychology of video games. Since May 2018, they include extra content.

Why it’s wrong to kill the player character in The Hand of Fate.

Read more...A rant about why bigger game worlds aren’t necessarily better.

Read more...

The Amiiqo is a recently announced device that can be used with an Android phone or tablet to back up and restore data from Amiibo figures. This data can easily be shared online, which means that the Amiiqo also effectively enables piracy of Amiibo.

Amiibo have only been around since November 2014. They aren’t the first major toys to life franchise - Skylanders came out in October 2011 and Disney Infinity launched in August 2013. (U.B. Funkeys in 2007 was a bit before its time, and I’m not sure when Hero Portal started because it’s not even on Wikipedia.) They all use similar technology (Amiibo uses NFC while others use RFID) and can thus all be backed up and pirated in roughly the same way. While the Amiiqo is not the first toys to life backup device to be announced (see, for example, MaxLander) it’s the first targeted specifically toward Amiibo and is getting more attention.

Why would Amiibo piracy be so much more interesting than Skylanders or Disney Infinity figure piracy? While Amiibo are in many ways similar to those franchises, there are several key differences that encourage piracy.

Read more...The debate has been over for a while now. Video games are art.

I knew it was over not when the National Endowment for the Arts added grants for games, or even when the US Supreme Court ruled that video games are protected speech. I knew it was over because of a newspaper clipping my grandmother sent me.

It was from a column called “The Arty Semite,” and it discussed the then-upcoming Biblically-inspired game El Shaddai: Ascension of the Metatron. (Full post here.) It didn’t make the argument that talking about heavy stuff like the Bible sure is artistic. It didn’t claim that this represented a step forward in the expressive significance of video games. It just said hey, here’s an interesting upcoming game. In a column about the arts.

In other words, my grandmother sent me a newspaper clipping that took it for granted that games are art. That’s how I knew.

Why was this debate so long-lived and vitriolic? “Are video games art?” seems like such a straightforward question. The problem is that it’s really two very different questions. The first is, “Is the medium of video games capable of artistic expression?”

This is the more useful question, and also the simpler one. It’s a matter of definition - if your definition of art precludes interaction (as did Roger Ebert’s) then video games can’t be art. Period. It’s not a judgment on video games, or an insult, or anything remotely offensive - it’s just the logical implication of the terms involved. It’s just what the words mean.

My answer to this first question is: “Yes, duh, of course the medium of video games is capable of artistic expression. Games can be beautiful, they can impart emotion, they can convey messages. What more do you want?”

The second question is, “Have any video games yet been made that can be considered profound works of great art?”

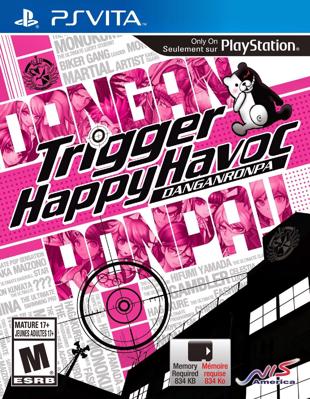

Read more...Danganronpa: Trigger Happy Havoc is overrated.

The game is basically fine. It oozes personality with a distinctive aesthetic that’s serviceable at worst and compelling at best. It boasts some clever twists and well-done mysteries. It’s also a bizarre mishmash of mechanics, some of which work and some of which don’t (the “Re: Action” system is flat-out the worst attempt at conversation branching I have ever seen in a game) featuring paper-thin characters and a bevy of plot holes. (There are also a few moments that are shockingly insensitive or offensive, but that’s another story.) It borrows heavily from influences including Ace Attorney, Zero Escape, Persona 4, and Battle Royale, but almost always in shallow ways that fail to emulate what made them great. The end result is entertaining, flashy, and kind of dumb.

[Gamasutra:] A lot of the characters fit into really strong stereotypes. The concept of being “The Ultimate” whatever means they stand out as stereotypes. Can you talk about why you went in that direction?

[Game Producer Yoshinori Terasawa]: What were we thinking about? It’s hard to answer that! [laughs] The scenario writer, Kazutaka Kodaka, he’s the one who basically thought of those stereotypes, and he created those characters. He’s the one who thought it up. When I spoke to Mr. Kodaka, I requested that he make [the player character] Makoto as non-special as possible, and make the other characters stand out in their own way a lot, and that’s why there’s this balance. That’s how Mr. Kodaka was able to create these characters.

Unlike a lot of other visual novels, there are a lot of other gameplay elements such as free exploration, and the trials having multiple different gameplay elements. Did that grow from the story or did those ideas come first?

YT: It was originally a basic visual novel, but visual novel games are not that popular in Japan anymore, either. So we figured that if Dangan Ronpa were to be just a visual novel, it would not be as popular we wanted it to be, these days. So that’s why, in order to show that the game is really interesting, we decided to add a lot of different features – after the scenario was written.

—Christian Nutt, Dangan Ronpa: Death, stress, and standing out from the crowd

Still, there’s a ton of potential here. If they’ve learned from their missteps, the sequel could be amazing. So we just have to wait for the Danganronpa 2: Goodbye Despair reviews, right?

Read more...

Some time later, I thought of taking up the axe again, rescuing my dusty guitar from where she was languishing in the corner of my bedroom. I got another nudge in this direction when a musically-inclined woman on OkCupid called me out on my profile photo where I’m holding a guitar. (“Can you actually play, or is that just to impress the ladies?” “It’s to impress the ladies. Is it working?”) Then Rocksmith 2014 went on sale and I read a glowing review of it, and I took the plunge.

(Incidentally, this is the first game I’ve ever played where I thought, “Man, I actually wish I were playing this with a Kinect.” It’s obnoxious to have to take your hands off the guitar and grab a controller to do basically anything. It would be amazing to be able to just say “Riff repeater, 50% speed!” and have it drop into the riff repeater at 50% speed.)

The game advises you to play for an hour every day, which I tried hard to stick to. Daily play was easy enough to achieve, but I didn’t always manage to last a full hour. At first, it was because I felt like I was learning a lot very quickly, and needed to take a break to digest. But after a few days, it was because I was getting frustrated.

Read more...In December of 2012, I played a game called Little Inferno. My purchase followed that of my friend Iceman’s, and both were due to Chris Franklin’s video on the subject (warning, total spoilers):

(By the way, if you aren’t familiar with Chris Franklin’s work, I highly recommend you rectify this situation.)

The game isn’t perfect and one can argue over the price point for a 3-hour experience you’ll probably never revisit, but it stuck in my mind and left me thinking. The obvious reading of the game is an attack on freemium games of the time-and-money-sink variety. I think one could make a pretty strong argument that its themes apply to games or trivial entertainments in general. But for me, the game is about growing up.

Read more...

So he enlisted the aid of Mama Professor, who took him to Toys R Us. With maybe fifty dollars to his name, Brother Professor surveyed the $35 NES games, inspecting the boxes of the games he did not already own. He found the one that looked the coolest, boosted by its ties to Greek mythology, and took it home. Unfortunately, Athena was the game inside.

When he began playing, my brother quickly realized it was an awful, awful game. Graphically ugly with no plot to speak of, featuring poorly designed levels and suffering from major control issues, the game didn’t even have any real connection to Greek mythology besides the name.

Brother Professor tried hard to like the game. It had been a major investment, and who knew when he could afford another one? But Athena was just too horrible. He couldn’t do it. He gave up. From then on, there was a self-enforced rule in the Professor household: rent before you buy.

Decades later, I was talking to Mama Professor and asked if she remembered when my brother had bought that one awful, awful game. “Athena,” she said immediately. I was impressed she remembered the title so easily. It turned out she remembered much more than that.

She’d been watching my brother inspect the game boxes. She knew this couldn’t possibly be a good way to pick out a game. She wanted to tell my brother to check reviews or talk to someone who had played the game. She wanted to forbid him from buying the game until he knew it was good. But she didn’t.

My mother held her tongue, and let my brother make his own mistake. And thus instead of resenting her treading on his freedoms, he learned a valuable lesson. A lot of parenting, my mother said, is knowing when to keep your mouth shut.

Fundamentally, an achievement is just a publicly-viewable checkmark indicating the completion of a particular action. The Xbox 360 added points gained from each achievement that accumulate into a total across all games. The PlayStation 3 followed suit, as did Apple’s GameCenter. (Notably, Steam did not. Steam achievements have no point value and do not add to a cumulative total.)

In order for these points to be meaningful, there has to be some kind of equality across games. The 360 mandates that each full retail game must provide exactly 1000 points worth of achievements (it’s a bit more complicated than that, but for our purposes let’s keep it simple). The PS3 has a similar rule, though its numbers are obfuscated (for convenience here, I shall refer to their point value as also 1000). This prevents oneupmanship between game developers, who might otherwise put out games with ever-increasing amounts of achievement points available, which would quickly render the running total meaningless and destroy much of the marketing value of achievements.

So what happens when a game launches with bad achievements? It’s become standard for games to be patched, but it’s unusual for achievements to be patched, and even then it’s generally just to avert controversy via a cosmetic change. Because of the need to keep a consistent point total, you can’t add new achievements without removing old ones - and removing or replacing an achievement is almost certain to upset people. No matter how ludicrous the achievement, somebody out there has it - and they don’t want the proof of their hard work stricken from the record. If you leave it up on their profile but make it no longer available for new players to get, then the new players may feel slighted that the opportunity to earn it has been taken away from them.

But the inability to add new achievements is severely limiting. It means you can’t fix problem achievements (of which there are plenty). It also leaves out a powerful way to grow a game - just look at how Valve has kept Team Fortress 2 fresh by adding, among other things, batches of new Steam achievements. (Steam achievements don’t have points, so they can freely be added without running afoul of point imbalance.)

Read more...

Probably the people watching my street racing movie like fancy cars, so they will appreciate the scene with the villain’s car. But now suppose I make another movie about a small-town high school teacher rallying the community for a local cause. When I first show the teacher driving to work, I use the same cinematic tricks I did in the other film - slowly panning along the car while playing dramatic music. Then the teacher gets to the school, and the story moves on.

Someone who really likes cars may still enjoy this scene, but to most people it’s going to be distracting at best. The car isn’t important to the story at all - why is it receiving so much attention? Why would I assume that the audience of this completely different film would be into cars? If I keep doing this, with more and more films on various subjects all treating cars in this same way, people who don’t care about cars may start to get annoyed with my work. They might feel that I’m being exclusionary in my film-making, privileging part of the audience over the rest for no clear reason. Plenty of people aren’t obsessed with cars - why can’t they enjoy my low-budget monster movie or my railroad magnate biopic too? Why do I insist on shoving in these totally distracting segments that damage the experience for them?

Read more...Recently, your friend and mine Cliff Bleszinski wrote an essay defending microtransactions in general and EA in specific. There are a lot of things to be said about this essay - some of which are said expertly by Jim Sterling here, and some of which touch on concepts discussed by Shamus Young writing a couple of years ago about Bobby Kotick here and here.

Read more...In games where the player character has a specific goal - save the Princess, escape the testing facility, defeat a nemesis - the player is presumed to share this goal. But even if the narrative does a good job lining up player motivations and character goals, there’s still a wrinkle. The character wants to accomplish something, and the player wants to experience accomplishing that thing. This is why we bother playing games at all, rather than just watching the endings on YouTube. If the player had the exact same motivations as the character, they’d cut whatever corners they could to beat the game as quickly as possible.

The humor in this video comes from the tension between Mario’s goals and the player’s goals. Of course Mario would want to just warp straight to the Princess and save her immediately. But for the player that would mean skipping the entire game, which would completely defeat the purpose of playing it in the first place. As long as Mario has that warp whistle in his inventory, there’s dissonance between what the player wants to do and what Mario would want to do.

So what happens when games create that dissonance on purpose?

Read more...GameStop Underling: Huh. That’s interesting.

GameStop Boss: What is?

Underling: These Deus Ex: Human Revolution games Square Enix shipped us include a voucher for a free OnLive copy of the game. I don’t think they mentioned they were gonna do that.

Boss: What? OnLive? But we just bought our own digital delivery game service - Impulse! That makes OnLive our competitor!

Underling: I suppose it does.

Boss: We better open the boxes and remove the vouchers.

Underling: Wait, what?

Read more...Recently we discussed Blizzard’s announcement that they are saddling Diablo III with terrible DRM, which they say isn’t DRM, but which everyone knows is DRM. I mentioned that there was much to be said about the contemporaneous announcements of a real-money auction house and a ban on modding. Well, the time for that is now.

Read more...You may have heard that there’s been a bit of a kerfuffle recently in response to some news about Diablo III. I’ll walk you through it - but first, we need to talk about Ubisoft.

On July 28, Ubisoft reported that they consider their constant connection DRM scheme to be a “success.” This despite the uproar and backlash caused by the scheme, the fact that it was immediately cracked, the clear demonstration of the system’s flaws when denial of service attacks locked out paying customers and left pirates unaffected, and Ubisoft’s eventual scaling back of the DRM to a once-per-run validation. Their reasoning?

Read more...Part One is here.

Anonymous said…

Post an update….what do you think of the replies you’ve got here?

Okay. You’re on.

Read more...I quit World of Warcraft in June of 2009. I quit hard. I donated my assets to the guild bank and deleted all of my characters. I didn’t want to leave the door open to come back. I wanted to burn it down and salt the earth.

Why? Well, that’s a bit complicated.

Read more...I don’t have much more to say about Uncharted 2, as it turns out, because I didn’t get through much more of it before giving up and sending it back to GameFly. I’m therefore not qualified to review it, but I’ll tell you that the reason I sent it back was because I disliked (a) the combat (b) the parkour (c) the artifact-hunting, which leaves very very little to enjoy. All that remains is the game’s cinematic components, the dialog and characterization and set-pieces. And there’s the other problem: Uncharted 2 is, even more than its predecessor, far too movie-like.

Read more...I’ve been thinking a lot lately about franchises. Having recently played Mass Effect 2, and then Assassin’s Creed II, and now Uncharted 2, I have a lot of questions about what sequels are and what they should be.

When I played the original Mass Effect, I fell head-over-heels in love. I made three complete play-throughs in rapid succession, I devoured both novels available at the time (Revelation and Ascension), and when called upon to name my favorite three video games, Mass Effect made the cut.

Then I played Mass Effect 2, and now I barely care about the series. I mean, I’ll probably play Mass Effect 3. I guess. Certainly not for full launch-day price. You can bet I won’t pre-order, even if they don’t pull any of my pet peeve shenanigans.

What happened here that turned my devoted fandom to near indifference?

Read more...